ART THAT MAKES HERITAGE. SWEDISH AND BELARUSIAN PERSPECTIVES ON ART AND HERITAGIZATION

10/24/2019

By Chiara Valli, in collaboration with Alina Dzeravianka and Elina Vidarsson

What is the role of art in changing societies? This question, at the core of the STATUS project, has certainly been asked and answered numerous times before by artists, philosophers, and intellectuals in different fields. Often, the answers dealt with consciousness and awareness: through artistic sensibility and aesthetic expressions, artistic practices provide new, unexpected connections and perspectives on the world.

What could our contribution be, answering the most existential question in art history: what is the role of art in changing societies? As a multidisciplinary group of female cultural workers, artists, and social researchers, we chose to delve into the question in dialogue with one another, by experimenting with ways to work together across disciplines and our diverse epistemologies. We chose to leave the comfort zones of our individual research methodologies, and to embrace dialogue, connections, and togetherness to come up with answers that would reach out in breadth, rather than focusing on inward looking, in depth individual research. Instead of centering our investigation around the personality and condition of the artist herself, then, we instead started reflecting about our general consciousness and ways of knowing the world. How are our consciousness formed? What do we see when we experience the world and think of ourselves in it? What do we take for granted? How are our collective identities formed? And finally, how can art shape those perceptions and ways of knowing?

Our perceptions of the world as individuals cannot be discerned from our experiential baggage, from the contexts we come from, and from the representations of those contexts. All those legacies constitutes our heritage. Heritage, as a way of interpreting and knowing the world, is seldom questioned or challenged, but rather it is taken for granted as a backdrop for our actions and choices. If art is about challenging accepted knowledge and representations, and offering fresh perspectives on the world, then, how can art change society by changing our heritage? Ultimately, how can art change the future by changing our perceptions of the past?

These questions guided our collective investigation efforts, whose ongoing outputs are presented below.

Some conceptual points of departure

Heritage is a complex and controversial term, but a common broad definition is: “[a]ll inherited resources which people value for reasons beyond mere utility.”1 More specifically, cultural heritage can be defined as “[i]nherited assets which people identify and value as a reflection and expression of their evolving knowledge, beliefs and traditions, and of their understanding of the beliefs and traditions of others.”2

We adopt an approach to heritage that comes from the academic field of Critical Heritage Studies. In this tradition, ‘heritage’ is not conceptualized as a set of objects or given entities, but rather as a process; heritage is always made through social and cultural collective processes that are always political.3 The process through which objects, practices and places are attached with values and transformed into heritage (or objects of preservation, display, and exhibition) is called heritagization4.

Somewhat counter intuitively, heritage-making is much more about the present than it is about the past. By being a process and a practice, heritage is “constantly chosen, recreated and renegotiated in the present5, to the point that it has been defined as “a production of the past in the present.”6 The past is brought and made alive into the present “through historical contingency and strategic appropriations, deployments, redeployments, and creation of connections and reconnection.”7

There are important distinctions, hence, between “the past (what has happened), history (selective attempts to describe this), and heritage (a contemporary product shaped from history”8Heritage “is thus a product of the present, purposefully developed in response to current needs or demands for it, and shaped by those requirements”9.

Understanding how heritage is produced and negotiated, hence, is a way to understand the present power relations and conflicts over the affirmation of identities. Heritage is used “to construct, reconstruct and negotiate a range of identities and social and cultural values and meanings in the present.”10 Importantly, these processes of reconstruction and negotiation of identities are sociopolitical processes that reflect the power structures of the society they are embedded in. The negotiation of the meanings of heritage is “a struggle over power (…) because heritage is itself a political resource.”11

Still, what is commonly acknowledged as heritage, i.e. what is valued as an official expression of the culture of a nation and displayed in public space as monuments, museums objects, fine arts, and reliquaries is also accepted as of unquestionably valuable, its importance supported by historical self-evidence and as a testimony of a neutral, and often glorified past. This process of removal or cancellation of the political, dialectical, conflicting dimensions of heritage is problematic because it reproduces homogenized, hegemonic representations of society, excluding minority, conflicting, dissonant, and individual voices and identities.

In urban areas for instance, the architecture and the display of historical layers becomes a normalized backdrop for people’s daily activities, so that the political struggles that shaped and constituted our cities become “hidden in plain sight”. As urban heritage is uncritically accepted and normalized, it can become a tool for authority making, unconsciously reinforcing hegemonic powers.

Heritage, art and political action

“Aesthetic experience has a political effect to the extent that the loss of destination that it presupposes disturbs the way in which bodies fit their functions and destinations. What it produces is… a multiplication of connections and disconnections that reframe the relation between bodies, the world where they live and the way in which they are ‘equipped’ for fitting it. It is a multiplicity of folds and gaps in the fabric of common experience that change the cartography of the perceptible, the thinkable and the feasible. As such, it allows for new modes of political construction of common objects and new possibilities of collective enunciation”12

How can art contribute to challenge and revert authoritative ways of making heritage? How can art make more plural, inclusive, democratic present and futures, by working with history and the past?

If, as it is often stated, art is a tool for bringing up dissonance and dissensus, by using aesthetics to make the invisible power plays visible (Rancière), art can also destabilize the often taken-for-granted notions of the past, and make their conflicting political connotations visible. This goes, of course, also for those political conflicting layers that are “hidden in plain sight” in our streets, squares, parks, museums, and public spaces.

Based in two national contexts, Sweden and Belarus, we collected a selection of examples where the arts have explicitly worked to challenge typical notions of the past, helped unpack the normalized superficial notion of heritage, and revealed it is as a mosaic of dissonant, alternative histories which result from political struggles. Interested in the generative power of art beyond its critical capacities, we also included examples where art is used to actively make heritage. To this purpose, two artist members of our group, i.e. Ingrid Falk and Linda Tedsdotter, engaged their own artistic practices to perform heritage-making in participatory ways, and explored some distinctive ways in which some selected histories should be preserved for the future in order to become heritage.

The art and Heritage catalogue

Our collection of examples of art and heritage practices can be read according to different themes and interpretations. Here, we propose a transversal reading that follows three red threads that examine what art does with/for heritage. These three threads are 1) art contesting authorized heritage; 2) art making hidden heritage visible; 3) art making heritage. The distinctions are not clear-cut and two or more motivations can coexist in each project or actions.

1) Art contesting authorized heritage

Peter Johansson, FAMILJETERAPI (Family therapy), 2018. Permanent installed on Alma Löv museum in Östra Ämtervik, Photo: Matti Östling

Peter Johansson, Final Solution to the Problem of Sculpture, 1990-92. Photo: Tord Lund

Peter Johansson, Full fräs!, 2016. Photo: Matti Östling

Irony and sarcasm have long been used in art to provide social and political critique, challenge traditions, and sedimented representations. This is the case with the whole production of the Swedish artist Peter Johansson, who targets right-wing nationalism by semantically appropriating and distorting symbols of national Swedish tradition and identity, like the Swedish flag, traditional red and white wooden houses (“stuga”), the popular sausages kiosks.

Marina Naprushkina, Patriot, 2008 (http://office-antipropaganda.com/wordpress/category/work/)

Marina Naprushkina, Office for Anti-Propaganda, 2011 (http://office-antipropaganda.com/wordpress/category/work/)

In Belarus Marina Naprushkina (who now lives in Berlin) uses appropriation of style, symbolics and hollowness of the current regime ideology of Belarus to question the current issues and politics of the state. In 2007 Naprushkina created the “Büro für Anti-Propaganda”, i.e. a research and documentation project which investigates how manipulation and control are used in nation-state of Belarus.13

Kopparmärra. Photo: Elina Vidarsson

Kopparmärra. Photo: Elina Vidarsson

“Daddy come home”. Photo montage: Kalle Boman and Ruben Östlund

The Square. Photo: Elina Vidarsson

Moreover, artists and cultural producers have sometimes led protests and debates around controversial monumental heritage, especially when exhibited in public urban spaces. One example is the art project “Daddy come home”, which deals with the relocalization of Kopparmärra, an equestrian statue of King Karl IX in the city center of Gothenburg. The debate about the statue relocalization was initiated by the Swedish film director Ruben Östlund and Kalle Boman, film professor and film producer, who questioned the monument’s relevance and what it represented. The monument on Kopparmärra at Kungsportsplatsen depicts Karl IX, father of Gustaf II Adolf. Ruben Östlund proposed to move Karl IX statue next to his son Gustav’s statue on Gustaf Adolf’s square, outside the City Hall of Gothenburg but in a less central place. The statue, they argue, represents a history that should not be romanticized. Therefore the king should not stand on a pedestal and should be removed or at least moved to a less central square. They also proposed to add the statues of Gustav II Adolf’s mother, Kristina, and perhaps the daughter, Queen Kristina, in the name of gender equality.

On the spot where Kopparmärra now stands, Östlund wants to create an art installation connected to the art project “Rutan”, a white square in Värnamo and which is supposed to be a place where people help each other and take responsibility for common rights and obligations. In the square people should be able to ask for help but also leave some objects, without them disappearing. “The square is a symbolic place that resembles our shared responsibility and builds a common agreement. The square can become a new landmark in Gothenburg to agree on (…) because from this box we do not steal.” A building permit application has been submitted to the municipality and the question is currently being debated.

Horse in a coat exhibition by Ruslan Vashkevich, Brest, 2016. Photo by Roman Chmel

Horse in a coat exhibition by Ruslan Vashkevich, Brest, 2016. Photo by Roman Chmel

Horse in a coat exhibition by Ruslan Vashkevich, Brest, 2016. Photo by Roman Chmel

The value of art objects themselves and the artistic heritage exposed in museums can be questioned and challenged by artists. “Horse in a coat” is an art project on borders and contraband, which was created specifically for the Brest museum by the Belarusian contemporary artist Ruslan Vashkevich. Contrabanded objects of Modern Art confiscated by Brest customs officers had to play the role of an invader and colonizer of the museum space in order to mix the perception of familiar objects and their functional purpose.

The project was first planned to be shown in the museum, but after museum professionals saw the objects, they refused to go on with the exhibition. The artist had to find a new installation place in one day. He found a place in a shopping mall, which added extra provocative tone to the project. The Museum of saved values (Музей спасенных ценностей) is the only museum in Belarus where works of art and antiques confiscated by Brest customs officers in the attempt to be smuggled abroad are exhibited. The main questions are: how is a collection formed? What is the value of the smuggled objects? Why do they became a museum objects? Ruslan tried to put critical view on the exhibited museum objects. Most of the objects he collected for the exhibition are the same objects as in museum but with some added artistic value. Then, what has more heritage value? The confiscated art objects per se, or the objects created by artist Ruslan Vashkevich?

2) Making hidden heritage visible

Political actions about making heritage is often achieved by adding, bringing to light, highlighting, uncovering and telling stories and legacies that have been neglected or silenced in the authorized heritage discourse. Typically, it is the legacies of women, minority groups, dissident communities that are silenced, repressed and erased from our common memory. We found contemporary examples of art and craft projects that worked to make some hidden forms of heritage visible through aesthetic practices and community engagement.

Kryly Halopa theater. Brest Stories Guide, 2017. Photo: Roman Chmel

Kryly Halopa theater. Brest Stories Guide, 2017. Photo: Roman Chmel

Kryly Halopa theater. Brest Stories Guide, 2017. Photo: Roman Chmel

Brest Stories Guide, by Kryly Halopa theatre (2017) is a project at the intersection of art, tourism, and cultural heritage preservation, the result of the co-work of about twenty people, including historians, Jewish organizations experts and Brest theaters actors.

The project consists of an audioplay about the the anti-Semitic manifestations since 1937, the Brest Jewish ghetto and the obliteration of the Jewish community in 1941-1942. This tour around a “nonexistent” Brest is based on materials from archives, books, photos, and interviews with survivors and other witnesses. Unpublished reports of German officers from the archives were also used. The play becomes a kind of investigation with the hearing of witnesses in the case of anti-Semitism and the Holocaust in Brest in the 1930s and 1940s. Now Brest has a history told not by the authors of textbooks and the creators of heroic narratives, but by its inhabitants. The mobile application consists of an audioplay and a city map which allow the user to navigate freely on the map with key places of Jewish heritage and historical events. Streets, buildings, and yards become a stage on which the voices from the past sound. The “Kryly Khalopa” theatre offers the viewer/listener to plunge into the history, and also see the outlines of a disappeared Brest through the face of today’s city.

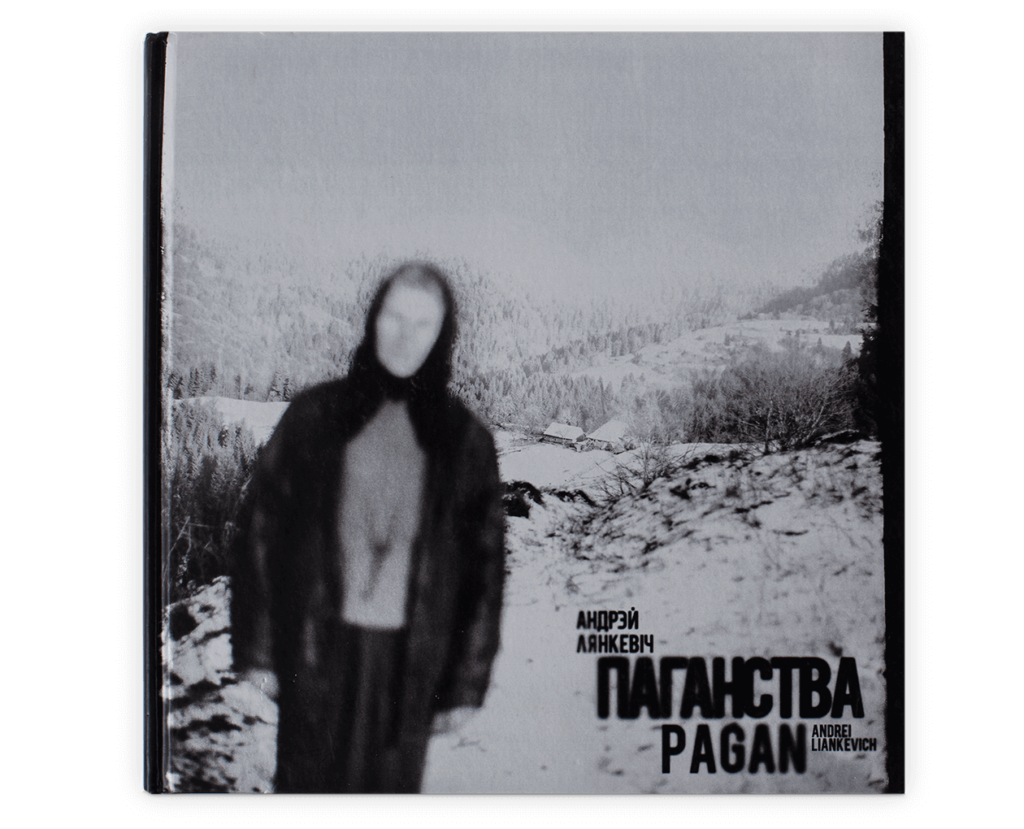

From the photo book Paganstva / Pagan by Andrei Liankevich

From the photo book Paganstva / Pagan by Andrei Liankevich

Photographic documentation can be a powerful tool for bringing to light hidden histories. In Belarus, pagan traditions are rapidly disappearing, also because of the affirmation of Christian cult and the influence it has had since the 1960s-70s in Belarusian society. The photobook Paganstva by Andrey Liankevich (2010) collects and shows some of the pagan traditions and customs that still exist in Belarus. The book came from the artist’s conviction that living in the Christian tradition, we do not always understand that these traditions only appeared after thousands of years of pagan beliefs and taboos. Traces of paganism and superstitions are still present in modern society, especially in rural areas. Liankevich’s book brings this popular cultural heritage back to attention and attends to its memory preservation, also by challenging the hegemony of Christianity as the main and only cultural reference for modern society.

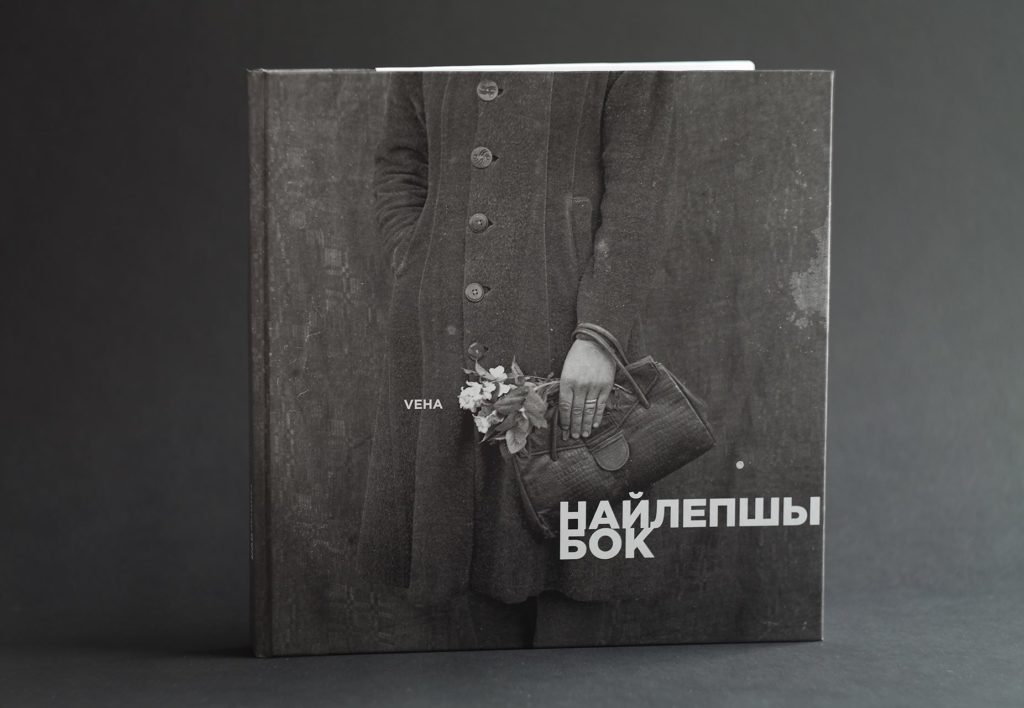

The Nailepshy Bok / The Best Side by VEHA

VEHA. Installation at the exhibition Heritagization. Gallery 54, Gothenburg, 2019. Photo: Denis Romanovski

Personal heritage is political heritage, too. During the Soviet and Post-Soviet times, collecting and treasuring family photo archives was not an encouraged or widespread practice in Belarus. The emphasis was put on collective social history rather than personal, family histories. The VEHA project, initiated by a collective of artists based in Minsk and the art director Lesya Pchelka, is dedicated to the preservation of family photos archives in Belarus and deals with the renewal, analysis and reconstruction of family archives. Through printed and digital archives, it helps creating value around family history and encourages to get a better understanding of one’s identity, roots, personal heritage.

Similarly, personal and private practices like handicraft, most often conducted by women in the private spaces of home, can become political acts and challenge male domination of public space and artistic expressions. A form of “craftivism”, Guerrilla-knitting “takes that most matronly craft (knitting) and that most maternal of gestures (wrapping something cold in a warm blanket) and transfers it to the concrete and steel wilds of the urban streetscape”14. Guerrilla-knitters have a feminist orientation, distance themselves from consumerism and give new light to the hand-made, labor-intensive production.

This is an international movement (in the Global North, at least), but it is a particularly widespread phenomenon in Sweden since the early 2010s. This is an example of alternative heritage making because it seeks to reinterpret the traditional handicrafts of knitting that historically has been performed by women in the private space of their homes, and bring them out to the streets. It also represents a soft and warm feminist critique to the heritage of the male-domination in the graffiti art subculture. In Sweden, it is particularly interesting because it also represents a way to get around the zero-tolerance policy against graffiti art. The guerrilla-knitting group Masquerade based in Stockholm states: “We often have political messages, but sometimes we don’t. Once, we decided to celebrate Sweden’s few female statues by dressing up four of them as superheroines.”15 This is a form of criticizing the male-dominated authorized heritage in Sweden through arts and crafts.

3) Art making new heritage

Finally, the generative power of art can not only make existing heritage and legacies visible, but can be active promoter of new forms of heritage, some to be actively made and preserved for the future generations. This is often rooted, of course, in existing traditions and history, and the fine line between preserving the existing heritage and making new one is difficult to draw. However, we collected here some examples where the arts have proactively contributed in generating heritage for the future by adding new values to existing objects, places, expressions, and hence revealed them as unedited forms of heritage.

The Shoreline memorial. Installation at ArkDes, Stockholm, 2018. Photo: Elina Vidarsson

The Shoreline memorial. Installation at ArkDes, Stockholm, 2018. Photo: Elina Vidarsson

The Shoreline memorial. Photo: Elina Vidarsson

The Shoreline memorial is a raised stone with a plaque engraved with “Spela Shoreline”. The monument was put up in a large park in Gothenburg (Slottsskogen) by two anonymous artists in 2014. The monument is dedicated to the memory of the Swedish alternative rock band “Broder Daniel” and placed on the site where the band had its final concert in 2008. However the city’s Park and Nature Administration wanted it removed because it was put up without legal approval. This provoked a huge social media response. Both the public and celebrities argued for its value. A Facebook campaign was created to convince the city´s Park and Nature Administration that the public wanted the monument to stay. Just after two days, the campaign was joined by 5000 people. After some time the political board of the city´s Park and Nature Administration made a formal decision to let the monument stay in the park. Four years later the rock is at a temporary exhibition called “Public Luxury” at the museum ArkDes (Sweden’s National Center for Architecture and Design) in Stockholm.

This case constitutes an interesting example of art making new heritage for several reasons: first, it elevated a piece of contemporary culture to the role of heritage through the traditional semiotic tool of the monumental object, yet it did it from a grassroots perspective, which managed to catalyze large grassroots popularity through contemporary social media. As one of its anonymous creators put it: “It is not a dusty sword bearer or sad bust of any Czech poet who no one read. It is contemporary history and speaks to the souls of Gothenburg´s people.”

It is a memory of the Swedish youth subculture “Panda Poppare” which is inspired by Brit-pop and pop art. Some also call (or rather called) themselves “BDpoppare” where BD stands for Broder Daniel, one of the most popular bands of the subculture. So it is interesting that a subculture that more or less died with the breakup of the band, is in a way materialized through this monument. From immaterial to material cultural heritage.

Finally, the case raises the question of the fetishization of art and the gentrification of grassroots artistic expressions. This monument, in fact, has done a “class journey”. It came from the bottom, was challenged by the decision makers and was approved from the top. And now it is on tour in the capital on one of the finest museums and part of the exhibition Public luxury.

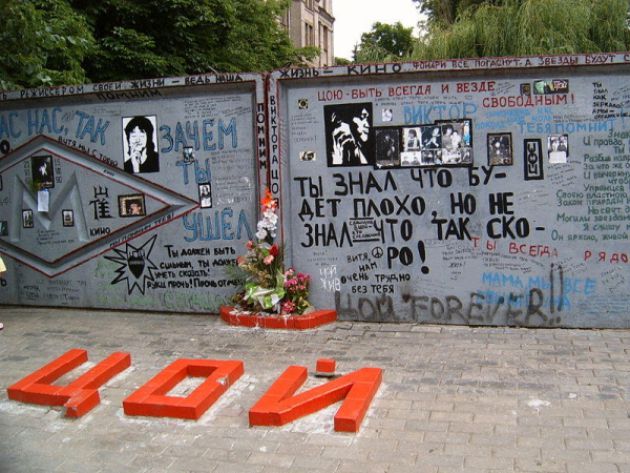

The wall of Tsoi, Minsk, 2019. Photo: Alina Dzeravianka

The wall of Tsoi, Minsk, 2019. Photo: Alina Dzeravianka

The similar grassroot initiative exist in Minsk, Belarus – it is the wall of Tsoi. The wall of Tsoi is a monument dedicated to the famous rock musician Viktor Tsoi (music band Kino), and it was installed in the Lyakhovsky Park in Minsk. In 1990, after the death of Viktor Tsoi, the wall appeared on the concrete slabs of October Square in the heart of Minsk. There were different marks, writings, pictures of musician left by his fans. In 1997 the most of the plates were removed, but the remaining two were moved to Internatsionalnaya Street, that is still the centre of Minsk. In 2010 the wall was restored in the park near the Dynamo stadium close to the university dormitories. It is still a popular place to hang out for people from subculture around Tsoi and band Kino. However the Viktor Tsoi is often associated with the marginal subcultures. One of his songs about Change was once forbidden for public listenings and radio because of its revolutionary mood. So like with the case of Shoreline memorial, the wall panels of Tsoi were created by bottom-up initiative, but then preserved and still kept by the city authorities despite its controversial meaning.

Kulturtemplet. Photo: Kjell Caminha

Kulturtemplet. Photo: Kjell Caminha

Butoh dancer Yuta Uno. Photo: Jorge Alcaide

Entrance of Kulturtemplet. Photo: Elise Yinzi Winqvist

Another example is Kulturtemplet, an old water reservoir at Gråberget in Sweden that was closed down for over 70 years until one day when a musician found this place. He walked inside and noticed that the reservoir had an amazing acoustic. Since that day he has been trying to turn the reservoir into a “contemporary temple to worship listening and emptiness.”

Finally, it is important to shed attention to how artistic practices and producers are involved in processes of urban valorization and heritagization that often result in the negative effects of gentrification. There are many examples of this, but we here mention the process of acknowledging the neighborhood of Haga, in Gothenburg, as protected heritage. Haga was planned to be demolished in the 1970s. Through protests that saw a large involvement of artists and cultural workers (in the late 1970s-1980s, it was the core of the punk music scene in Gothenburg), it became acknowledged as heritage and saved from demolition. Now it is one of the most gentrified areas in Gothenburg. This is an example of how well-intentioned processes of heritagization in urban spaces often become co-opted and become instruments for gentrification. There are several cases that could be brought up, but this is a striking one on the ambivalence and risks that heritagization processes can bring about, even when they start from grassroots initiatives.

A similar example in Minsk is the the Oktyabrskaya street and its development of former factory area into bars, creative spaces, and cultural consumption amenities. At the beginning of the 20th century it was the industrial outskirts of Minsk and place for the factory MZOR dealing with steel and factory machines. But by the 2010s, a process of revitalization had started there. First the photo gallery Znyata opened together with cafe NewTon. In 2012 a bar Huligan was opened, and the street became a lively place in the city life. In 2014 at Oktyabrskaya the street art festival Vulica Brasil was organized that created the first big murals on the walls of a former factory and an independent art venue, CECH, moved in. Nowadays part of the premises were bought by the bank for future development, more and more restaurants opened here, as well as hotels and offices. The destiny of local, small businesses and artistic spaces reflects a well-known path in cities around the world: priced out, they are swiftly displaced by more remunerative activities. Like in Haga in Gothenburg, the well intentioned process to revitalize the abandoned industrial area became a starting point for gentrification.

Our art practices: making heritage

Two artists in our group, Linda Tedsdotter and Ingrid Falk, created ad-hoc original artistic contribution to our common research on art and heritage-making.

Linda Tedsdotter in her project ‘Apocalypse Insurance-Waterproof–A Selection of Art History’ questions: what shall the future of art history include?

Linda Tedsdotter. Apocalypse Insurance-Waterproof – A Selection of Art History. Installation at the exhibition Heritagization. Gallery 54, Gothenburg, 2019. Photo: Denis Romanovski

Linda Tedsdotter. Apocalypse Insurance-Waterproof – A Selection of Art History. Installation at the exhibition Heritagization. Gallery 54, Gothenburg, 2019. Photo: Denis Romanovski

Linda Tedsdotter. Apocalypse Insurance-Waterproof – A Selection of Art History. Installation at the exhibition Heritagization. Gallery 54, Gothenburg, 2019. Photo: Denis Romanovski

She offered other artists to send her their books and catalogues, to manifest what should be preserved as Art History. Linda also emphasizes that she works with a series of pieces based on the idea of herself as an artist prepper. She tries to use her artistic work to secure the potential dark future we are facing. In her works she tries to answer the question: What do I need as a person to survive, and how can I use my present work to help out in different future scenarios and at the same time express the obvious damage we all participate in.

For the exhibition in Gothenburg at Galleri 54, in March 2019, she collected artists books, vacuum packed them and piled them on a floatable “pallet”.

In this artwork Linda contributes to the topic of art, contesting authorized heritage. With this work we are forced to think about who should decide what Art History includes and how the present artists will be presented in the future.

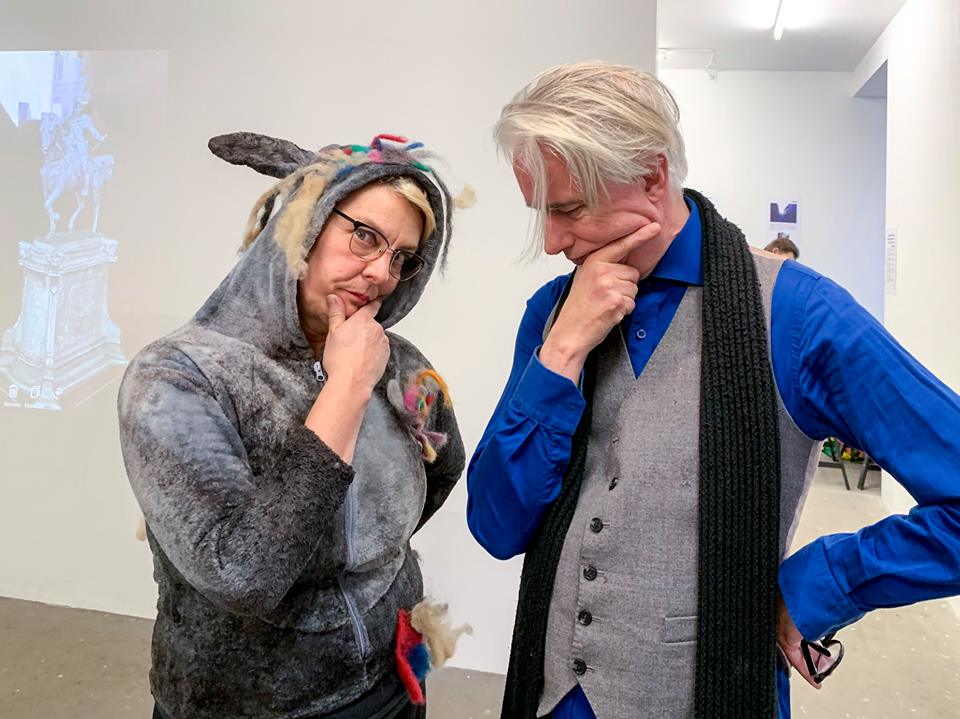

Ingrid Falk. Rabbit Ingrid. Performance at the exhibition Heritagization. Gallery 54, Gothenburg, 2019. Photo: Denis Romanovski

Ingrid Falk. Rabbit Ingrid. Performance at the exhibition Heritagization. Gallery 54, Gothenburg, 2019. Photo: Denis Romanovski

Ingrid Falk uses a performative practice to work with the topic of heritagization. She goes public and uses questionnaires to gather audience reflections on the issue of heritagization and the role of cultural workers. In her practice, she takes on the twofold roles of the “research rabbit” and “cockroach-parasite”. A rabbit was chosen because it is a domesticated animal that is sometimes used for contributing to human activities, while a cockroach is a parasite, is not useful in any conventional ways and does not contribute to society in most cases.

Having these two roles on her, Ingrid wanted to question and reconsider what is meant by heritage now, and how society and smaller communities can contribute to the heritagization process.

In her questionnaires, she asked adults and small children the following questions:

1) What do you like doing most of all? Some activity? Something you do in company or would do if you had some others to join you? Is there anything you think you want to tell the children of the future about? Why? What is special about ‘doing’ ‘making’ ‘saying’ or ‘action/activity’?

2) Is there something (object) – a tool or a toy – that you are particular fond of? Is there an object you want to tell the children of the future about? Why?

3) Is there a place – around here – or somewhere else – that you are particularly fond of? Is that space or place or building important to save for the children of the future? Why?

4) What do you think heritagization can do? What is your proposal for a heritagization-process?

5) Do you have any idea what artists do today? What do you think artists should/could do today?

You can read more about the findings in Ingrid’s article. Maybe by reading these questions you can try to answer them for yourself and then think about the future we create, taking something from the past and present. What we see as a heritage should be a constant discussion and reflection.

Concluding remarks

The presented artistic interventions constitute moments of heritage politics, because they challenge in different ways hegemonic, authorized heritage discourse. They articulate alternative ways of interpreting collective memory and social imagination, and by doing so they make heritage more plural and inclusive. In this way, even when not explicitly, they commit to emancipatory heritage political actions. By making the invisible visible, by contesting what is taken for granted, and by creatively proposing alternative imaginaries for the future, artistic practices can impact our perceptions of reality and have a role in shaping how societies can change.

-

English Heritage 2008:71↩

-

English Heritage 2008:71↩

-

Tunbridge, Ashworth 1996, Harvey 2001, Smith 2006↩

-

Walsh 1992, Harrison 2013↩

-

Rodney Harrison. Heritage. Critical Approaches. London: Routledge, 2013., p. 165↩

-

Rodney Harrison: Heritage. Critical Approaches. London: Routledge, 2013., p. 32↩

-

Silverman, Waterton, and Watson, 2017, p. 4↩

-

Tunbridge, Ashworth 1996:20↩

-

Tunbridge, Ashworth 1996:6↩

-

Smith 2006, p. 3↩

-

Smith 2006, p. 281↩

-

Jacques Rancière. Aesthetic Separation, Aesthetic Community: Scenes from the Aesthetic Regime of Art. In Art & Research. Volume 2, # 1 Summer, 2008. See http://www.artandresearch.org.uk/v2n1/ranciere.html#_ftn1 Accessed 15 March 2019

2008, p. 13↩

-

More details on Marina Naprushkina works are available http://marina-naprushkina.de/ ↩

-

Wollan, Malia (2011). “Graffiti’s Cozy, Feminine Side” in the New York Times https://www.nytimes.com/2011/05/19/fashion/creating-graffiti-with-yarn.html. Accessed 21 December, 2018 ↩

-

Rotschild, Nathalie (2009).“Sweden: Where graffiti is prohibited, urban knitters make a new street art” in the Christian Science Monitor https://www.csmonitor.com/World/Global-News/2009/0922/sweden-where-graffiti-is-prohibited-urban-knitters-make-a-new-street-art. Accessed 21 December, 2018