In February 2022, I started working with the Swedish theater ADAS in Gothenburg on a play called Mama Zoya, Belarus. Through conversations and interviews with my mother Zoya, this play sheds light on her fate, her struggle to achieve her dreams, and the tragic impact of mental illness. And, besides this, about trauma, love, feminine strength, and human life in difficult historical and political circumstances.

The project ended sadly for me. I was suspended from work by the Swedish side. And I was also excluded from my very personal statement, which was supposed to be a declaration of love for my mother.

A brief overview of my background. My experience in independent theater in Belarus spans 23 years. I work as an actress and director in my own theater projects. Someone may know that in Belarus, independent projects may not receive funding, especially if they are included in ban lists by the KGB and ideological departments. Despite this, the Kryly Khalopa theater remained one of Belarus’s most renowned, enduring, and successful touring independent theaters. The KX Space in Brest was established by the theater group in 2014 and has since functioned as a gallery for contemporary art and a platform for cultural events. It was one of the most important independent cultural centers in Belarus. KX was a partner in numerous international projects, and their numbers were only increasing. All these years I led both the theater and the space, which were closed by the Belarusian authorities in 2021. Over the last 6 years, the team consisted entirely of women who shared a similar mindset. Such a situation as happened to me in Gothenburg has never happened in my life before. I am used to thinking of myself as a professional, one of the few female directors in Belarus, and quite a successful one. My Swedish partners tried to make me believe that I was unwell and not suitable for work. Nevertheless, I chose to interpret the events through my own perspective.

My interest in postcolonial studies, combined with three days spent in May 2023 at the Humboldt Forum in Berlin studying the ethnographic collection, helped me understand and reflect on the history of the Swedish-Belarusian project Mama Zoya, Belarus. My numerous meetings and conversations with Belarusians who live in exile, as well as the Kurdish diaspora in Sweden, have made it possible to see the gap that exists between the proclaimed European values and what is happening in practice. A critique of inequality, of the idea of productivity and working conditions in the capitalist system served as another starting point for my reflection.

Some may say that I am making an excessive claim by utilizing tools like this and using words like “colonial” in seemingly unconnected contexts. Perhaps, I might have found more suitable definitions. However, it seems to me that the use of the term “colonial” outside the usual usage nevertheless expands its meaning and allows it to be used in a situation like what happened to me in Sweden.

PROJECT ZOYA: CHRONOLOGY

November 2021, Gothenburg

I’m flying to Sweden for a month of art residency as part of the Swedish-Belarusian project Status. The Swedish colleagues planned to search for Swedish partners to collaborate on projects with Belarusian artists. This is how I meet actress and director Fia and ADAS Theater. It seems that we wouldn’t have found a better partner: a small private theater in Gothenburg deals with very similar topics — women’s stories and feminism. Fia expresses a keen interest in doing something together.

I was very tired at that moment, so I refused. We have just completed the play Frau mit Automat and had the premiere in Poland. It was finalized in Germany and Poland because my theater in Belarus was closed by that time. In the same year, the Department of Financial Investigations came to my house to initiate a criminal trial. I went through searches, interrogations, and the very real possibility of going to prison. This is one of the repressive measures applied to NGOs and media in Belarus after the 2020 elections. I got caught in the gears of a strict educational system, dealing with the challenges of being a mother to a teenager who found themselves in a difficult situation. I faced pressure from the school, the police, the juvenile commission, the prosecutor’s office, and others I can’t even recall. This was followed by the closure of KX Space and my theater in Brest, along with many other non-profit organizations. Antidepressants keep me going. Fia, on the contrary, radiates with energy and enthusiasm, this enthusiasm scares me, and I brush it off even more desperately.

February 2022, Brest

I return to Belarus, several months have passed. As I walk through a snowy forest, I suddenly think about my plans with the Swedes, and Fia’s energy reminds me of someone. I decide that the only thing I’m willing to do with her is a play about my mother Zoya, who has the same fierce power. I return to Zoya’s house, brush the snow off my boots, and turn on the recorder for the first time. And a little later I sent Fia a letter.

Letter to Fia and who is Zoya

16.02.2022

Dear Fia!

I am thinking now about a performance about my mother. About her – she is a really unusual woman for post-Soviet reality. She was like an “usual” in Soviet time- normal patriarchy family, she worked in the factory and had all the homework and 2 kids… When the Perestrojka started she decided to prove to her husband that she is great and brilliant. Because she can’t forgive how he considered her much lower than himself professionally and said this openly in front of his friends. She decided that she will become rich! And started to go on shop-tours to Moscow and Warsaw with huge bags… and it was terrible, really terrible and hard. Then she started her own business, and I can call her a very brave self-made woman. She has no higher education but she worked like an economist in big enterprises in the 90-th… and finally she gave me and my brother financial stability… and 10 years ago she gone mad, her nervous system broked. Last 10 years I have patronized her and seen her flat- it looks like the scenography for a performance or film…

What I see in this — the story of a woman who fought with patriarchat by her own method and it was extremely hard. And where there is a lot of controversy in it, for example her heroine and ideal was Zoya Kosmodemjanskaya, the Soviet heroine who was killed by fascists… She’s really incredible though giving me a lot of worries now.

I talked with Sveta and she agrees that you are the best performer for this role. Also the “mother” topic is important for you, Fia. So I would like to direct the performance with you as an actor.

I started to interview my mom. Playwright I usually work with is ready to help me with the text.

So what do you think , Fia?

Warm hugs,

Aksana

February 21, 2022

Excitedly, Fia answers “yes” and suggests being the playwright for our project. Together, we will construct it through our dialogues and written correspondence.

May 2022, Gothenburg

I am coming for the second month of my residency in Gothenburg. We start working on the text, gather together, and have conversations for 3–5 hours. I tell about my mother and my family, the Soviet Union, the war, and today’s Belarus. The Swedes are not Poles; they know almost nothing about us. During my journey, I engage in research and read extensively about the daily life of the Soviet Union, as well as other topics that I need to explain to someone unfamiliar with our past and present reality.

I am happy that Fia is so sincerely interested in my history and the history of my Belarus. This is a genuine interest, and I have also discovered a lot about my family’s history. We become friends.

Summer 2022, Brest

I record new interviews with my mother and transcribe them into text. After that, Sveta translates them into English. Sveta is an actress and the manager of the Kryly Khalopa Theater and my closest friend, with whom we have been working together for more than 15 years.

I found my mother’s “Turkish diaries”, several thick notebooks. In 2009, Zoya went on vacation to Turkey and did not return. The initial severe onset of the disease occurred while she was at the airport. She remained there for a week, having very little food, and documenting her experience continuously. Then I took her from Turkey and thus began the story of her illness and my custody of her.

I transcribe and translate the diaries, which read like a horror script, into English for Fia.

September 2022, Vitlycke and Gothenburg

The next session with Fia takes place in a beautiful forested area north of Gothenburg. We only have a week and a half to work, we work 8–10 hours a day.

Fia is extremely productive, which makes it challenging for me to keep up, but I’m managing. I look at my Swedish friend and realize that she is over 60 years old, which is 20 years older than me, but she is much stronger. Through discussions with my friends, we have collectively concluded that my physical decline is a manifestation of necropolitics1 and the challenges of enduring in a politically tumultuous environment.

We are creating a scenario plan. Now it has the working title The Three Lives of Zoya, and my mother’s entire life is divided into three parts: childhood, marriage, madness and her experience at the Turkish airport. The history of the country where Zoya lives plays a big role in the script. I love creating stories with multiple layers and weaving performances that span different dimensions: private and political, real and mythical.

We return to Gothenburg and continue to work. We begin to discuss the cast and production process. I immediately refuse to perform in the play; it is beyond my strength to work on the material and perform. Fia persistently suggests a second actress, Lisbeth. It’s clear to me that producing a play where the majority of the script revolves around young Zoya, with two actresses over 60, will be quite challenging. I insist on inviting Sveta as the third actress, and I also want to provide the opportunity for Belarusians in exile to work. This raises questions, but the main concern is transparency (for the first time a word is uttered that will later haunt the Zoya project). Fia is unsure if the process will maintain its transparency considering the involvement of my Belarusian friend and actress, with whom I am very close. These doubts are unreasonable to me.

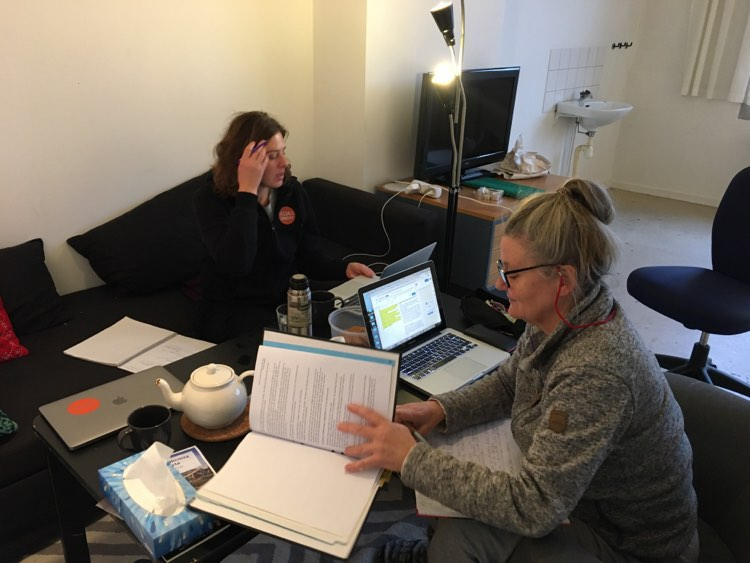

Sviatlana Haidalionak, Andreas Luukinen

October 2022, Brest

I am admitted to the hospital with persistent dizziness. Among other findings, I was diagnosed with an anxiety disorder and strongly advised to restart my use of antidepressants, which I had previously discontinued. A couple of weeks after being discharged from the hospital, I fly to Gothenburg for scheduled work with Fia.

November–December 2022, Gothenburg

Fia and I continue our meetings and work on the text.

At the same time, we are developing a budget and plan for the upcoming production process. Sveta arrives, we all work together. I insist on inviting a composer and set designer from Belarus to the project. All of them are professionals, among the best in the Belarusian scene, and they are all in forced emigration.

We are developing a concept for the work of our international team. We have decided that the participants will work in mixed groups. We are creating a budget. I have noticed that the fee for the Belarusian composer, Sergei (name changed), is half the amount of the fee for a sound engineer. I’ve been informed that the budget is very limited, and Jonas is an excellent specialist who cannot be paid less. It’s obvious that everyone is uncomfortable, but we decide to ask Sergei if he is ready to work for this money. The answer is predictable, “Of course, I’m ready!”. People in exile do not have much disdain.

We are drawing up a tour plan. As I understand it, our Swedish partners do not tour outside of Sweden. I extend the invitation to perform at festivals and with our partners in Poland and Germany, where my performances are much anticipated.

I found out that Fia received a grant for the text we are already working on. This is the most expensive task in the project; they pay more for this in Sweden than for anything else. I haven’t received anything yet except money for living expenses from the travel grant and residency, but the future final fee included in the budget suits me. It will cover my work for a year, I think.

January–February 2023, India

I’m going to India on a long-awaited vacation, but the text of Mama Zoya is not finished yet. I am receiving texts from Fia for editing. We are pressed for time, and production work must commence by the end of February.

During that time Swedes receive money for the production — less than they wanted, but the desired minimum was met!

In mid-February, the draft of the play is completed.

February 2023, Gothenburg

We start on February 27th. The whole team meets in Gothenburg: four Belarusian participants and six Swedish ones. We only have 2 weeks for table conversations, introductions, text discussions, assignments, and questions, and 5 weeks for the production. And we deal with very complex and multi-layered concepts.

The atmosphere is very tense, some might even say nervous. From morning until evening, we are in the theater, and rehearsals begin in the second week.

It’s hard for me. Everyone looks at me expectantly, and all the time there is a feeling that they are dissatisfied with me. I’m trying to find an approach. I have a lot of adaptability. Dealing with censorship, financial struggles, and years of activist theater with no funding, collaborating with diverse communities, navigating the shift to online work due to COVID-19, facing repressions, and constant crisis management — I have learned to find solutions in the face of any challenge. But it seems like I am always doing something wrong here. Suddenly, there was a shift, and amidst all the overwhelming stress, I was finally struck with inspiration. I stay up until night, building the concept of the play, and the work goes on!

Very soon, I start to feel unwell. This is psychosomatics: I know how my body behaves when I don’t get enough rest and time. My back is in excruciating pain. Insomnia begins. I heighten the doses of my pills, consoling myself that the journey will be short and I can persevere through it. I somehow recover on the weekends, but after a few weeks even the weekends don’t help.

The relentless speed and pressure to be productive as quickly as possible isn’t just taking a toll on me. After a while, the whole team begins to feel unwell. Fia doesn’t sleep at night because her husband is sick. One day she gets into an accident and breaks her car. The pressure and stress are increasing and:

- I am reminded that I must reply to letters during weekends — our schedule is tight, and we are expected to be accessible on Sundays as well. However, after experiencing burnout in 2014, I made the decision to stop working on Sundays.

- We live with Sveta; in fact, there is never an opportunity to be alone. At the same time, Fia has complaints: we are likely discussing the performance together, and this lack of transparency is not good!

- In an effort to be more efficient and productive, I assign tasks to Sveta, the main character in the first part who has the most challenging role. Individual task assignments have always been the norm in our theater. We now live in the same apartment and can work from home. There are complaints about this being “not transparent” again.

- It is not allowed for us to speak Belarusian, even if I need to briefly explain Sveta’s task to her. This provokes a storm of anger. At the same time, everyone is comfortable speaking Swedish, indicating Lisbeth’s limited knowledge of English as the reason.

- We dedicate a significant amount of time after rehearsals to thoroughly explain the play’s developments to all team members, including for some reason the costume designer, set designer, lighting designer, and others. Fia complains that the two of us need to have more discussions together.

- Fia decides to use my free morning time for this purpose. All of a sudden, with no prior notice, just hours before rehearsals, she starts showing up at my studio, which is conveniently located next to the theater. I begin to live in constant anxiety and anticipation of a persistent knock on the door. After a few morning visits, I ask Fia to let me have some time alone during my free time — it’s crucial for my recovery, which I really require. Fia apologizes, expresses gratitude for my openness, and within 3 days, the cycle repeats itself.

- I require some time to focus on the script independently. I request more time for myself because otherwise, I’ll have to stay up late at night. Fia says she assumed I would take care of it while I was in India — which is puzzling considering the script was released just 2 weeks before production.

- Fia is even busier with other important meetings. But in a time when we could be doing our personal work, (or, God forbid, relaxing), we are persistently offered to visit theaters, including children’s theaters. I attempt to decline, stating, “I have an appointment with my therapist!” — “Maybe you can reschedule?” Fia insists. “No!” I answer. With each passing moment, I am becoming more enraged by the pain and fatigue.

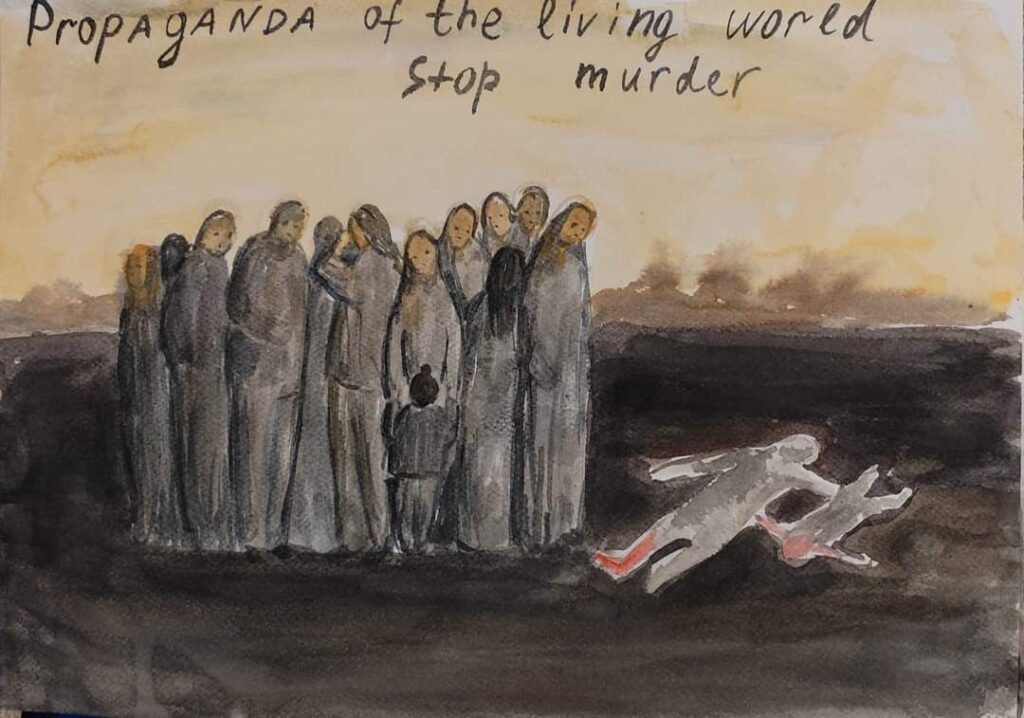

- My last rehearsal was marked by a hysterical outburst. During improvisation, Sveta suddenly starts crying when she hears the Belarusian anthem, which the Swedes play for inspiration. The Swedes begin to shout (yes, shout) at Sveta. They are yelling that they can’t work in these conditions, Sveta’s crying, which is not the first time interrupting the rehearsal, does not allow everyone to move forward productively! “Use your trauma!!” — they shout — “use it for our work!” Sveta is silent.

- Then I start to swear. As the director, I stand by Sveta and refuse to exploit anyone’s traumas. I intend to be cautious not only with Sveta but with everyone involved. I say that I am not Jerzy Grotowski, whom both Swedish actresses are so proud to know, and that in the name of brilliant production, I will not turn anyone into a corpse, as was the case with Ryszard Cieślak. After everyone has gone, I take a stroll in the park until nightfall. I’m furious.

March 21, Gothenburg

Upon waking up the morning after the scandal, I receive a text from Fia in which she expresses great concern for my health. She wants to come over and talk to me right now. The topic of conversation is solely my health, not business. She insists. That day, I must appear at the rehearsal at 13:00. I have decided that it will be better to stop talking for the sake of my health. I suggested meeting after the rehearsal, as I have asked to be allowed to rest in my free time.

Near 9 a.m., there is a persistent knock on the door, I don’t open it. At 12:50, I go out with my folders to the rehearsal and run into Fia on the doorstep. A scene takes place right in the corridor of my studio where she declares that the ADAS theater has decided to send me on a two-week vacation. Fia says that I am sick, unable to work, and I don’t have the director’s vision and the strength to lead. The theater has a significant financial responsibility and cannot afford to slow down the process because of me. I reminded her that two days ago she was happy about how well we were working. No! Badly! I insist that I can handle the job, and a two-week suspension is like leaving completely because there are only 3 weeks left until the planned premiere. I suggest going to the theater where the whole team is already seated and hearing everyone’s opinions; for me, this would be a reasonable decision. To exclude the director is an outrageous decision. “We don’t have time to talk about this,” Fia says. “You didn’t open the door this morning to talk! We don’t have any more time!”

I am being asked to leave the studio and not to communicate with Sveta. I will be moving to the apartment previously occupied by my colleagues from Belarus.

Through tears, I pack my things. In the evening I leave the studio.

March 2023, Gothenburg

Amid my “vacation,” I realize that I haven’t signed a contract yet. It looks like the contract has not been signed by anyone. I am writing a letter to the ADAS producer requesting that the documents be prepared as soon as possible. In Sweden, this is considered normal, he says. I am surprised by this unique Swedish approach because everywhere it is not normal to work without a contract. They finally sent me a contract to sign after a week, but the amount stated was only half of our agreed sum. In response to my question about the amount, they explain that I haven’t earned any more money due to my sickness.

According to one of my diplomas, I am a business lawyer. I observe violations and arbitrariness in this. I insist that the contract must be signed based on a prior agreement, and then we will determine what I have actually accomplished. Furthermore, I also want to point out that the proposed contract for donors may appear to be corrupt. It seems that the producer got scared, I got my way, and the contract was signed. I’m happy (in vain).

Sveta informs me that Fia is actively revising and modifying my decisions and developments in the play.

It won’t be long before ADAS Theater proposes to remove my name from the project, claiming it is for my safety in Belarus. I say that it is sufficient for my safety if all texts are first sent to me for approval before being published, and I request that this clause be included in the contract. ADAS is attempting to persuade me. A bit later I realize that they are trying to untie their hands. But a clause appears in the contract. There is also a clause stating that the ADAS theater does not bear any responsibility for any potential issues I may encounter with the Belarusian authorities.

Within 1 to 2 weeks, all my pain disappears.

April 3, 2023, Gothenburg

After 2 weeks, there is a meeting where Swedes ask me what I want to do. I do not get the question. After all, everything has already been thoroughly redone, and there is a week left before the planned premiere. There are no offers, everyone is waiting for something from me, it seems they are waiting for me to refuse. I refuse. I don’t understand how I can return to the theater where no one said a word in my defense, and I don’t understand what I will do in a production where my directorial decision has no meaning. And I myself mean nothing. Furthermore, I no longer understand the payment situation for my work, and I no longer have any guarantees.

April 15, 2023, Gothenburg

The premiere has been postponed. To bring the play to the premiere, a male Swedish director is invited, and everyone willingly follows his decisions. And even accepts his individual tasks for Sveta.

May 2023, Berlin

I don’t wait for the premiere; I fly to Berlin. I am sending a payment invoice for the contract. They inform me that I only earned half and try convincing me that this is actually very good money. All my further negotiations lead to nothing. I call for justice. I have been working on the project for a year, and my fee is almost equal to that of the sound engineer, despite the fact that this is my project, my idea, and my contribution to the production is immeasurably greater. They repeat that Jonas is a highly qualified specialist and, moreover, supervises his younger colleague from Belarus. I suggest that the donors and foundations that contributed funds for Zoya become a third party in our negotiations. However, the Swedes have stopped responding to my letters. What I continue to receive are declarations of deep and endless love from Fia. Nobody answers any of my questions anymore. I am not receiving the letters sent to all participants in the Zoya project. I don’t receive feedback forms about our work on the Zoya project, unlike all my colleagues (I remember the notorious lack of transparency).

My name as a director has been removed from the posters; now it’s only mentioned as the co-author of the concept with Fia. I’m almost invisible.

I’m flying to the last spring showing of Zoya from Berlin. The performance is not so bad, although my complexity, the most “exotic” ideas, and the wonderful music that we developed together with Sergei have disappeared.

On the last evening before leaving for Belarus, I was reading a Swedish post on Facebook about the play and nearly fainted. This text puts me at risk. It seems that the ADAS theater is not concerned about my safety, as nobody has sent me any texts as we agreed in the contract. I write a letter to ADAS, to which no one responds.

I am going to Belarus, and at the border, I am detained and interrogated by KGB officers. I have been outside the country for a long time, and I am on certain lists.

I’ve never received answers to my questions from ADAS Theater. The theater is bustling with preparations for the upcoming tour of the play and vacations.

CONCLUSIONS

What exactly happened? I had the chance to attribute all the problems to what might have seemed as Fia’s peculiar character, her workaholic tendencies, and perceived toxic work environment at ADAS theater. But I’m tempted to look deeper.

I decided to explore the difference between European ethical values and ideas and the actual decisions and actions that guide Europeans in their interactions with Others.

I turned to the texts of the Cameroonian philosopher Achille Mbembe, who advocates “the critique, not of the West per se, but of the effects of cruelty and blindness produced by a certain conception – I’d call it colonial – of reason, of humanism, and of universalism.”2

I thought about colonialism in connection with the Zoya project. Colonialism, after all, consists not only of seizing land, appropriating resources, establishing one’s own order in the occupied territories, etc. The main characteristic is the exploitation and use of resources, as well as making a profit in the capitalist market. My Swedish colleagues utilized me and my resources, and then deprived me of my performance, half of my fee, and basic safety.

The mistrust shown towards the entire Belarusian team from the beginning of the production process signaled that we were not considered good enough; we were seen as Others. The outcome was my exclusion, the halt of communication with the Belarusian composer and set designer after I left, the almost total dismissal of their contributions to the play, and the reassignment of Sveta to “students” being taught by Swedish actresses to perform “well and correctly.”

In their initial public communications about the Zoya project, the Swedes discussed the displaced Belarusians they encountered and expressed their strong desire to assist people who have lost their homes, homeland, and means of livelihood due to repressions. This is also colonial rhetoric: when Germany extracted rubber and ivory in Africa, the colonialists claimed their goal was to help the underdeveloped natives with their comprehensive development. “Colonialism constantly lies about itself and about others,” says Achille Mbembe.3

Our work was subject to rules that were supposedly democratic and pluralistic, but in fact, they became practices of subordination. We could be taught and treated as if we were savages who are not used to proper and productive work. We could have been shouted at outrageously. We were prohibited from speaking our own language, supposedly to promote mutual respect and transparency. However, this did not prevent the Swedes from using Swedish that we didn’t understand. In the end, our European colleagues took the right to PUNISH, grant the opportunity to work or exclude without discussion. To punish is a privilege, and I couldn’t oppose it because I was not in my own country or theater. I was also denied the opportunity to defend myself: they simply stopped answering my letters and made it seem as if I had disappeared and no longer existed.

“Colonialism was largely a policy of disciplining bodies, inextricably connected to the desire to increase their efficiency, pliability and productivity”.4 I turned out to be stubborn, too weak, undisciplined, and my theatrical concepts were too complicated. I had complex concepts. I didn’t shout or claim power, as a normal director supposedly should. Likewise, I prevented them from creating a fully commercial product and using today’s stories of Belarus due to the risk of repression.

The equal co-production that Zoya was supposed to be, became a project of exclusion and demonstration of power. “…postcolonial thinking, the critique of European humanism and universalism, is… carried out with the aim of paving the way for an inquiry into the possibility of a politics of the fellow-creature. The prerequisite for such a politics is the recognition of the Other and of his or her difference.”5 Recognizing the Other as different, but equal, opening up to the new experience that the Other brings, expanding one’s borders was beyond the power of my European colleagues. They decided that they could tell my story much better than I could. Instead of being open to the Other, they have chosen, in the good colonial tradition, to speak ON BEHALF of the Other.

It seems like I failed. But based on what Jack Halberstam writes in The queer art of failure, the best thing possible happened to me. Failure, according to Halberstam, can indicate the impossibility of functioning in a rigid capitalist system, “under certain circumstances, failure, losing, forgetting, not doing, not knowing can actually produce more creative, more solidary, more surprising ways of being in the world.”6 My failure in Gothenburg could be seen as a victory: I was able to leave the toxic project, maintaining myself, my health, and my dignity. All 9 of my colleagues at Zoya chose to remain silent, and I don’t blame them. They all have their own reasons to obey and support obvious injustice.

Finally, an indicative fact. During one of the sessions with Fia, I met a Kurdish man named Mardin. Persecution forced him to flee Iran. Mardin came to help me the same day I was expelled from the Zoya project, moved my things and helped me throughout the month that I lived in Sweden. Through him, I became a little acquainted with the Kurdish diaspora in Gothenburg and Stockholm. And something very important happened to me. For the first time in my life, I stopped identifying myself with white Europeans. I have never had any insecurities and have always considered myself equal to the people in any European country. I still consider myself equal, but now I associate myself not with the white Swedes, but with Kurds, Iranians, Syrians, Turks and other Others living in Gothenburg, on the opposite bank of the river — in Hisingen.

It is important for me to say all this today, and I regard my anger and my voice as the voice of a woman who was deprived of authorship in her own history, as the voice of one who was exploited and thrown out, as the voice of the invisible and nameless, of which there are millions in Europe today.

I recently read a novel by the Russian writer Oksana Vasyakina, “Wound,” which depicts her journey to bury an urn containing her mother’s ashes across Russia, all the way to Siberia. I read and thought that I was not successful in creating an art piece about my mother and my very personal story — something that Vasyakina did so well. I cannot consider the performance Mama Zoya, Belarus being my own. It seems that I’ll need to approach it differently; perhaps by putting on another play or penning a book. Regardless, I have faith that my artistic statement about Zoya will still happen.

2.07.2023

- Achille Mbembe, the Cameroonian philosopher who introduced the concept of necropolitics, defines it as the authority of those in power to choose which individuals within their jurisdiction are allowed to live and which are deemed unworthy of existence.↩

- Eurozine.com. (2008). What is postcolonial thinking? An interview with Achille Mbembe. [online] Available at: https://www.eurozine.com/what-is-postcolonial-thinking/.↩

- Ibid.↩

- Achille Mbembe (2001). On the Postcolony. Univ of California Press.↩

- Eurozine.com. (2008). What is postcolonial thinking? An interview with Achille Mbembe. [online] Available at: https://www.eurozine.com/what-is-postcolonial-thinking/.↩

- Halberstam, J. (2011). The queer art of failure. Durham ; London: Duke University Press.↩