– “What do I do?” – asked a young man from Petersburg, impatiently.

– What do you mean what should you do? If it’s summer – wash berries and make jam out of them; if it’s winter – drink tea with that jam.

Vasily Rozanov

National plans established for the next six months are usually quite predictable. Before 2020, autumn in Belarus was the time of dodging neighbor’s spare apples and zucchini, making fun of the government’s discours on crop yields, and constantly speculating about the upcoming winter. That was our everyday life – a simple and relatively happy life.

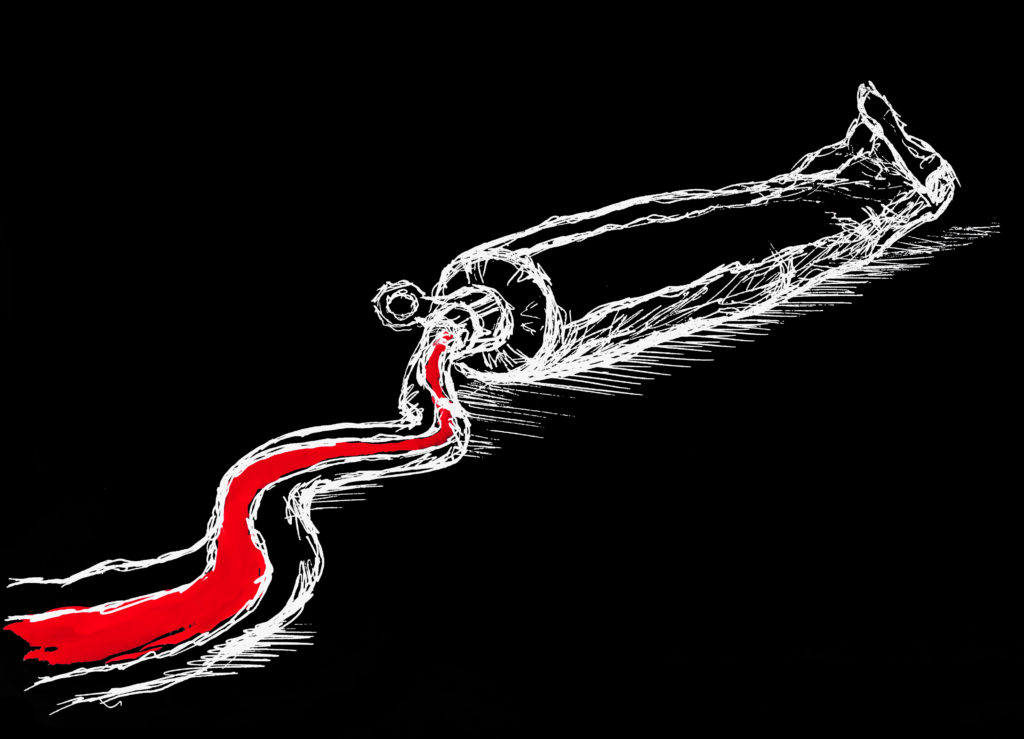

Everything changed when criminal trials, isolation wards, detention centers, and refugee crises became part of everyday life and entered mass consciousness. Both unjust imprisonment and fleeing to a foreign country first and foremost translates to the loss of a home. The evil strange will is overtaking our habitual spaces and the natural order of things and forcing us into the unknown where everything is unwanted and even hateful.

For myself and thousands of other Belarusians, the possibility of being at home has turned into a privilege, disrupting the very idea of how the world operates. Both politically motivated arrests and involuntary migration are rather traumatic experiences that can wreck one’s outlook on the world. It’s painful and destructive for the human psyche to be dehumanized when being checked into the isolation ward by having to take off every clothing article. And it’s not even the fact that you have to squat down while being naked in front of strangers; it’s the fact that with every squat you lose a bit of faith in a better world. As painful as it is to pack your bags hastily, not knowing if you’re going to see your apartment ever again. It’s painful to lose your relatively happy life.

How can we continue living without faith in humanity, with a shattered illusion of us being a highly developed civilization that values human rights? Return to the Old Testament’s “tit for tat”? Slim pickings. But the real terror prevails when behind your pain and a sense of despair you suddenly realize that for millions of people in other countries, this utter horror of living in an unfair world and unlimitely a dictatorship is their everyday life.

Guantanamo Bay, “the Boogieman” to an Arab boy

Recently I’ve started reading “Guantánamo Diary” by Mohamedou Ould Salahi. No state has ever had evidence that Mohamedou was involved in the attacks and the Millennium plot but this has not prevented him from being tortured and imprisoned for 14 years.

When I decided to share my impressions of the book with my friend in a refugee camp, I began by asking if he had ever heard of Guantanamo Bay. He laughed out loud and said that if you are born a boy in the Arab world, adults scare you with this prison from early childhood. The prospect of just being in a torture chamber for years is a “bonus” that is given to Arab Muslims at birth.

What do adults in post-Soviet countries scare their children with? Becoming a janitor if you’re not good at studying, falling in with the wrong crowd? Well, sounds like a fairy tale by comparison. Arab boys are being scared by their parents with flights in a cold compartment with a bag on their heads, regular beatings, night interrogations, months of isolation in solitary confinement without sunlight, torture by cold, hunger, and sleep deprivation.

Depending on where we are born – in which country, in which family, and in which religion – we are surrounded by a very different reality, but sometimes our very different realities intersect. While in theory this should make us develop a sense of empathy, help us understand each other, and globally make the world at least a little bit safer, in practice we see how things have developed with the migration crisis on the Belarus–Lithuania border. Spoiler: there are some serious problems with empathy.

The “good” and “bad” refugees

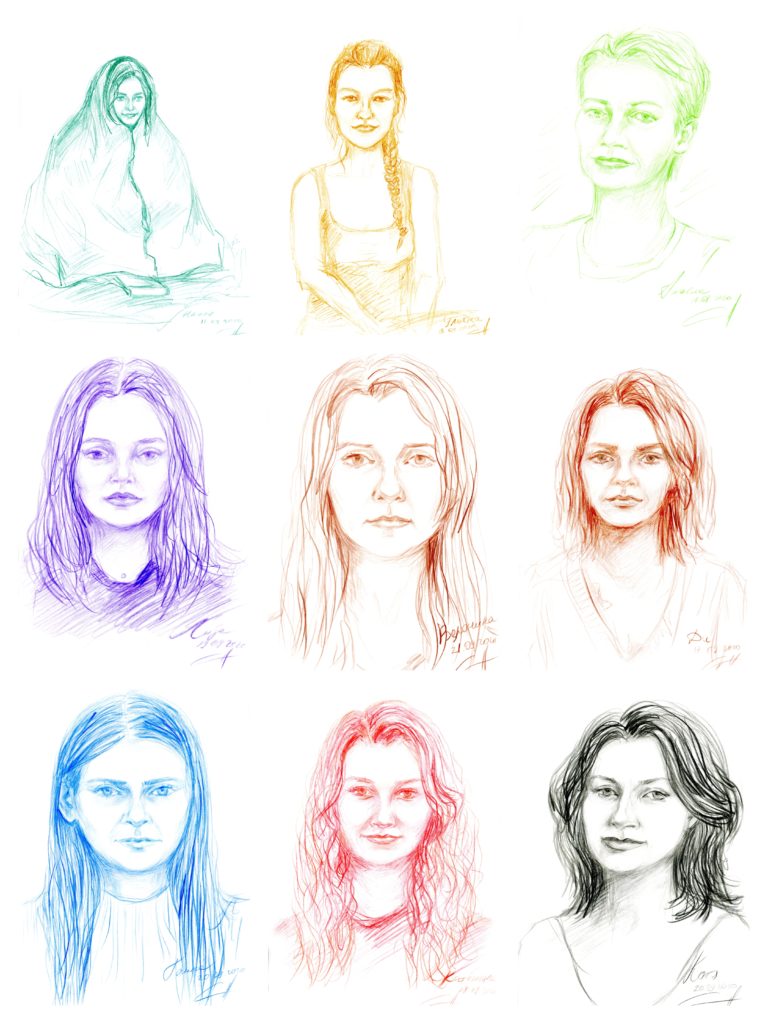

I ended up in a refugee camp in January 2021 after serving two administrative arrests due to my work as a protest journalist and receiving “special” attention from the Investigative Committee. When I settled in the camp, I was naively expecting to see some especially cordial relationships between Belarusians there and was a little cautious of potential misunderstandings because of cultural differences that I could have with men from Asia, African countries, and the Middle East. But things weren’t quite as I expected. My idea that Belarusians who fled the country would unconditionally support each other and show solidarity in every possible way was confronted by a reality in which there was a lot of aggression, gossip, and petty squabble.

Myths and legends about Great Belarusian Tolerance have been quickly dispelled by the locker room chatter. At first glance, it could seem that everyone in a refugee camp is on a nearly equal footing – far from home, with an uncertain future and a difficult background – and that based on this, everyone would understand and empathize with each other. In reality, though, the refugee camp looks more like an American high school from a coming-of-age movie: there are leaders and outcasts, popular castes and losers.

It’s not common to talk about the fact that in this brave new world Belarusians do not look like saints at all. That is because we care to maintain a certain image of Belarusians abroad and to not feed the propaganda media to besmirch Belarusians who flee the country. The culture of silence too can be found here – in the refugee communities and diasporas. Because of the image of an “ideal refugee”, which is so carefully imposed on the most ordinary and very different people from Belarus, and the simultaneous demonization of refugees from Asia, Africa, and the Middle East, racism and xenophobia are only gaining momentum.

And we are not talking about some unique Belarusian complex perception of the surrounding reality here. As the current migration crisis in Lithuania shows, the so-called European values and ideas about the equality of all human beings turn out to exist as a very thin layer of culture that instantly disappears when the “white European person” feels threatened by “these foreigners”.

On closer examination, however, it turns out that the very existence of refugees is already perceived by some people as a threat, and they spread this outlook in everyday conversations within their close circle but also in the media. “We need to find physically strong guys who will be in direct contact and able to respond in case of a critical situation. Everyone understands what I mean, there is no need to clarify,” says1 the Lithuanian who is against the

housing of people who illegally crossed the border in the district he lives in. Another resident adds that she is afraid for her children.

It’s important to note that most of the people, who crossed the Belarus–Lithuania border illegally and who trigger fear and rejection among locals, are Iraqi immigrants. But it is worth remembering that over the past year, Belarusians have also fled to Lithuania from the Lukashenko regime, and they were not called illegal immigrants and were not considered a catalyst for the migration crisis. And even more so, there was no material in the media where people escaping from Belarus would be spoken of as a source of danger for Lithuanian residents. Moreover, there were no regular status updates on how many Belarusians illegally crossed the border during the reporting period. And I don’t remember a single case when photos of Belarusians making their way to Lithuania outside the checkpoint were replicated in the media.

Are the Lithuanians afraid of people fleeing Belarus? Doesn’t seem like it. Does this say something about the refugees themselves? Also no. It’s just that the media and EU politicians initially classified Belarusians as “their own”, and therefore any information about the actions committed by Belarusian refugees automatically goes into the neutral category “what is happening in Lithuania,” and not into the criminal section “what refugees and migrants are doing in Lithuania.”

“You don’t understand, it’s different”2

Tens of thousands of people have left Belarus over the past year due to political repression. The absolute majority does not seek political asylum anywhere, and officially these people cannot be classified as refugees, although, in fact, they are.

In a situation like this one, it would be logical for Belarusians to massively support refugees from other countries. And I’m not talking about hands-on help or material support, but simply about the rejection of hate speech and xenophobia. However, numerous discussions on social networks and the reaction of people to news from the Lithuanian border show that everything is not so simple, and for many people, human rights and solidarity remain such “template” concepts. And this “template” concept manifests itself in the following: when our rights are violated in our homeland, we have the right to get international support and to save ourselves by any means, but Iraqis in a similar situation must silently endure all hardships and under no circumstances violate the rules of crossing state borders.

Why has such an unethical system developed in the mass consciousness where people are divided into “worthy” and “unworthy” according to ethnicity? It seems likely that it has to do with a distinctive remembrance culture. It’s common for us to idealize the past, the unresolved traumas of the 20th century, and even slavery during the times of serfdom, which many of our ancestors had experienced. And now, in new crises, we often do not show solidarity with Others but take revenge on them in an attempt to finally get such a desired experience of ruling and dominating.

This is a national-level hazing, caused by Nietzschean resentment – a feeling of anger, despair, and powerlessness directed at those whom one blames for one’s doom. It is mindless envy of the fictitious benefits that Middle Eastern refugees and migrants ostensibly receive. Interestingly enough, people with anti-migrant sentiments remain hostages of the same stereotypes and myths as the refugees themselves, who pay tens of thousands of dollars to the guides who pledge their help to move them to Germany. Both the Middle Eastern men crossing the border between Lithuania and Belarus outside the checkpoint, and those who hate these people, believe in the same thing – that refugees will find paradise in Germany.

And since we do not have access to this fictional paradise and cannot get real power over the people who flee from Iraq to the EU countries, we enjoy power on the level of verbal abuse. After all, running away from our native country, we often find ourselves at quite a low level in our new social hierarchy, and aggression and intolerance against refugees from other countries allow us to climb a little higher on the ladder. And therefore we are no longer at the bottom and not the main object of public mistrust, and the taxpayers’ money does not seem to be spent on us. On second thought, the money is spent though, but these expenses are mere trifles compared to how much money is allegedly spent on the maintenance of other refugees (in this case, Iraqis).

We explain our hostility, even hatred through noble motives: care for taxpayers and the economic well-being of the EU countries, a burden to objective justice, and other noble reasons – but these are only beautiful words to cover xenophobia.

Except xenophobia is not some kind of objective reality or predominant human trait. This is a way of seeing the world, and this way has its reasons and its internal logic. And when it comes to dividing refugees into “worthy” and “unworthy”, it is based on an existential dread of a huge, unfair world. It is as if we are trying to monopolize the right to pain and suffering, not ready to accept the fact that other people have it just as bad as we do, or even worse. Particularly, we are not ready to analyze whether we play any role in this universal injustice or whether we are responsible for the fact that Others are even worse off than ourselves.

People who don’t feel pain

“Close the door tighter to not let in the wind. Don’t open it too often. And don’t go outside. Don’t go farther than your stairway – there’s evil there. Anything farther from your house is evil because there’s indifference.”

Vasily Rozanov

When choosing a side in a conflict, we choose who we are more alike to. Whom do we have more in common with – white Europeans or refugees from poor dictatorial countries?

As the public reaction to the migration crisis in Lithuania shows, for the most part, we are not ready to move away from the biological approach and still put innate endowments higher in the hierarchy than acquired ones. We’d much rather identify with a white person from a European country than with Iraqis, even if we share with the latter the same kitchen in the refugee camp, and with the first, we are united only by the color of skin.

I say “we”/”us”/”our” all the time to not seem as if I’ve taken the moral high ground, and as if I am not part of this Belarusian discourse about “good and bad” refugees. I guess I don’t want to sound arrogant and build a distance between myself and other people who grew up with similar cultural attitudes. Perhaps, this is my way of trying to break the dichotomy of “us” and “them.” One way or another, I deliberately say “we”, bringing together myself, other refugees, and you – the people reading this text. Making us one group.

We all have common traits – both acquired and innate. And, most importantly, none of us have some kind of innate ability not to experience humiliation or the obligation to be content with little. But why do we, people from the Western world, evaluate the same actions of people from Belarus and from Iraq so differently? Why is a Belarusian who makes their way to Lithuania through fields and forests a hero and a successor of the partisans, who should be sympathized with and helped as actively as possible, and an Iraqi who has done the same is a threat to the European Union, a criminal and practically a horseman of the Apocalypse?

Firstly, a major role in these assessments is played by the propaganda machine, which in the case of Belarus has for many years cherished a monocultural society and literally prayed for its (this society) closed nature. Secondly, xenophobia is a legacy of the Soviet era, where, for example, with all the professed universal equality, in reality, certain educational opportunities were closed for the Jews, and everyday anti-Semitism was something completely ordinary. Thirdly, the unwillingness to understand and accept the Other may be due to the regular lack of resources and their struggle for them. In such conditions, anyone who is labeled as Others or Outsiders is considered a potential threat in the struggle for resources.

Based only on the fact that another person was born in a poor country, we deny them the right to have ambitions and dreams. After all, having dreams is even more of a privilege than having a home and hot dinners. Dreaming is possible only for “self-made men” who at the same time ignore the abyss of their existing privileges.

In most cases, anti-migrant movements and xenophobic sentiments, in general, are based on the division of people into those who deserve the best and have the right to move up the social ladder, and those who were born in a country “with such traditions”. According to some people, traditions are a basis for the requirement of what a person can and cannot feel, what one can and cannot dream about, and what one can and cannot aspire to.

I came across a map of the world online, where the regions are highlighted in different colors depending on how the media in Western countries react to the catastrophes taking place there. The hardest we, people from the Western world, take the death of people from rich and successful countries like the United States, Canada, and Western Europe, whilst the tragic news from India, Yemen, or Sudan, cause quite an insignificant reaction (if any).

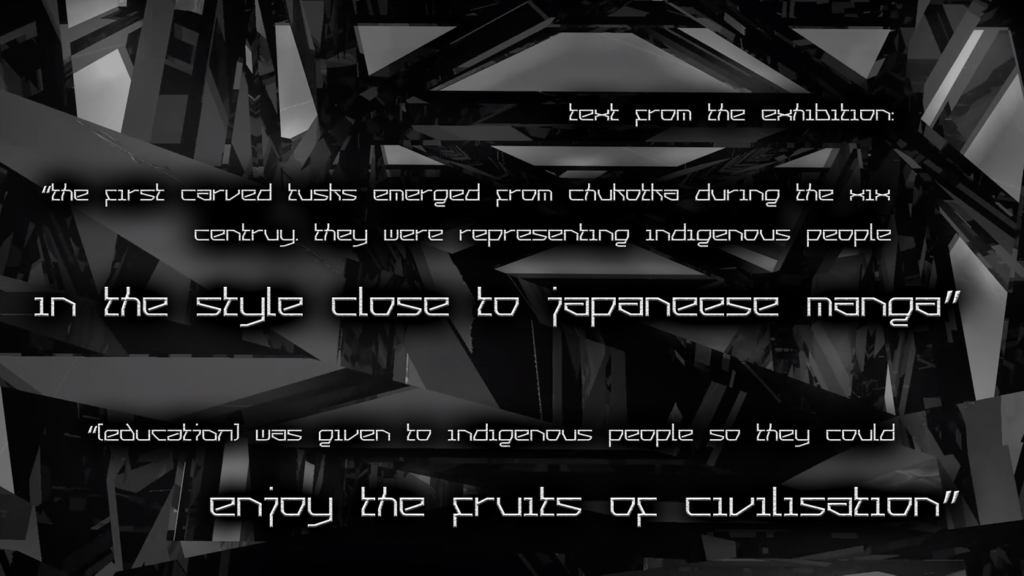

The same reaction follows human rights violations. Western media do not particularly pay attention to torture in Jordan, by default attributing everything to “their customs,” while photographs of men beaten at Akrestsina have spread around the world media in a matter of days. Living in the paradigm that there is a “civilized” Us and there is Them – “uncivilized” and “barbarians” – we justify violence against those who were not fortunate enough to be born into poor families of Iraq or Pakistan.

We say that prohibiting women and girls from going out alone is “just tradition”, and attempts to outlaw female genital mutilation are cultural expansion and the eradication of foreign customs. It’s as if there are women somewhere who are not hurt by the circumcision of the clitoris, and who are not harmed by total dependence on men. As if there are nations somewhere that are happy with living in a dictatorship. As if some in our world want respect and independence, and some are just fine with torture and war.

From this notion, which is based on an unwillingness to see and understand the Other, the idea arises that people from Belarus are the “good refugees” who have the right to save their own lives, while people fleeing Iraq are no refugees at all, but particularly dangerous elements who should be content with that they have, and live according to the principle “bloom where you’re planted”.

Such an idea, per se, is the result of long-time colonial policies, which doesn’t seem to apply to Belarus, although Belarusians strangely identify in their worldview with inhabitants of colonial countries. The mechanism of overcompensation is also instrumental in this case: in the political public discourse, media, and mass culture, Belarus is constantly presented as a small country and a kind of “not successful enough” version of Russia. For people who care about national self-identification, such comparisons can be offensive, and to overcome being in a position of humiliation, they try to find a space in which they can dominate. In the case of the current migration crisis, Iraqis fleeing their native country are a very convenient means for Belarusians’ self–aggrandizement.

In his “Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals”, the German philosopher Immanuel Kant wrote that rational human beings should be treated as an end in themselves and not as a means to something else. But seeing Iraqis stuck on the border only as a way to boost self-esteem and feel proud of our nation, opposing a foreign one, we only support our own insecurities and, once again, take the position of the humiliated and offended. Choosing condemnation over compassion, we reproduce this destructive pattern over and over again and continue suffering from it, long and hard. This is a spiral of violence, that is extremely difficult to get out of, and almost impossible if unaided. As such aid for the so-called laymen could serve journalistic materials and works of art, whose authors refuse to reproduce offensive stereotypes and demonize the Other.

It could be argued that for a deep understanding of the current situation with refugees, we don’t have enough historical distance and that we are too personally involved in this situation. However, precisely these alleged gaps can become an advantage for those who decide to reject the traditional discriminatory lens of looking at refugees and want to show the Other in their entirety, not reducing their complexity to one tragic fact of biography.

***

Below are a few comments on the news about the unrest in the refugee camp in Lithuania. According to the protesters, the reason for the unrest was the rain-soaked tents, poor food, and untimely medical assistance. There is a lot of dehumanization and hatred in these comments, and reading them can leave you feeling intense anger and disgust, as well as potentially being re-traumatized if you have had the experience of being a refugee. However, I think it’s very important that those with enough moral resources can read the real statements of real people, and not be limited here to just my interpretation.

-

However, vesti.ru, which published the comment about “tough guys”, is a biased source that contributes to spreading the stereotypes instead of reflecting on them. We can assume that the publication does this by accident or due to the lack of education of journalists working on the topic of refugees and migration, but the more plausible version seems to be that vesti.ru pursues its own agenda. They demonstrate the position of official Moscow, which is to support Lukashenka, in particular informationally.

-

An ironic phrase that has become a meme. It is used to emphasize the one-sidedness and inconsistency of the opponent’s position.↩