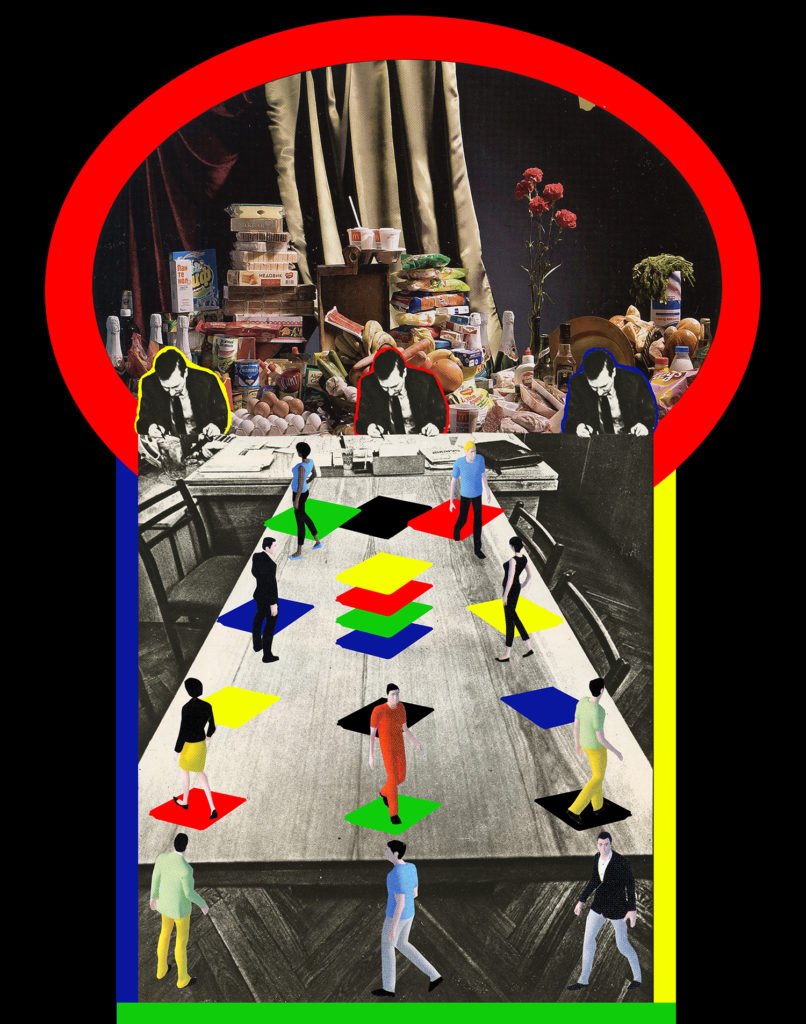

Illustrations: Masha Svyatogor, 2019

This essay is a result of a micro research, which was conducted with the aim of describing and analyzing the status of a male and a female artist (hereinafter referred to as an artist1) in Belarus with respect to the social, economic, and emotional dimensions of this work. First of all, I was interested in artistic self-identification, their interpretations of art, their work environment, and their means of production, and what their expectations for the future are. For the analysis, I used the data, which I collected through an anonymous questionnaire2 and private, informal interviews with the selected artists from Belarus who perform their activities in the independent art sector. By “independent”, I mean spaces of art that are not connected to state institutions, but operate on a freelance contract. However, the “independence” might include different modalities of collaboration with the state sector: participation in exhibitions, curatorial initiatives, temporary or permanent positions in state institutions.3 In my thinking, I also turn to my own empirical work experience in the art field (as a curator and an art critic). Initially, apart from the aforementioned topics, for me it was important to emphasize the experience of women artists. But in the process of doing so, it became clear that this issue demands a separate research; therefore in the supplementary commentary to the main text, I’m going to point out only certain aspects of a female artist’s situation and her work environment.

In the first part of the essay, I will present a variety of topics and issues, which interested me, and by grouping them together I will analyze the results I found. In the second part, I will summarize my conclusions comparing local experiences with global perspectives. I want to point out straight away that the framework that I set for the research (my focus on the independent art sector) covers only a certain segment of the Belarusian art field and my aim in this text is to create a fragmentary, horizontal description of this context by selecting new research to produce a more comprehensive analysis in the future.

My idea is that, on the one hand, the frustration that is typical for the Belarusian independent art field in the last years and the loss of artistic status happened as a result of globalization and capitalism arriving here. As it turned out, the art field, which lacks an internal support system and, due to a particular political climate, lacks an external system support, was not ready for these factors. On the other hand, the processes of rethinking how art functions and the dialectics surrounding its distinctions (between art as work and non-work), which are present in Belarus, coincide with the changes happening in Western countries, which demonstrates how Belarusian artists are integrated (intuitively or deliberately) into the global context.

Artistic Self-Identification and One’s Work Environment

Artists’ interviewed explained their choices (why they chose art as their profession?), listed the outlook that they had (“it worked out well”). They explained their parents’ impact on their choice (they were sent to an Art School) and the influence of their family (artistic) environment. They explained that their desire to become an artist was based off the perception that an artist is free from social limitations (which has been constructed by stories of successful artists in global art history).4 For example, for one of the artists who was interviewed, in his youth, he had the choice between sports and art because he achieved equally good results in both activities. But when he realized his limit – “the peak” – in sports, he chose art, which promised him unlimited progress. Art opened the doors to the great world, it seemed to be a practice of self-development (“it’s important to find… and perceive yourself in the process”), a laboratory that allows one to explore topics of interest, and to demonstrate political will. Art is freedom, a challenge (“for one’s ego”), an instrument for communication with the world, a possibility for wholesome self-realization, “it’s a drug addiction… it’s euphoria”, and an artist is a superhuman, who manages to exist on the outskirts of any system – capitalism or authoritarianism. Less commonly, the choice [to pursue art] was made at a conscious age, during or after receiving education. “…Art is one of the most complex things in the world. Because in math and science… you are judged according to some clear scale – oh, look, this machine is working…while art works differently… it’s more difficult to achieve recognition. Getting into that zone of recognition means conquering the highest peak.”

None of the interviewed artists wondered how art would provide them with financial stability when they had to choose their life’s path (“then you shouldn’t be engaged in art”). This issue seemed to belong to the career field, which they were trying to slip out from, “I just wanted to do what I love… to find the joy in life”, “I’ve never wanted to just make a lot of money”, “an artist’s life is hard… In my youth, few people thought and cared about careers.” The same interviewees who came to the art field after already having a different profession and a stable income, knew that it was impossible to earn by art and viewed this activity as a philosophical practice. “…And I saw how the lack of financial security made people think about money more often and as often as about art… People become victims of this system, where it is difficult to make money and it is almost impossible not just to make money but to live. I did not experience that, but I saw it around me… how badly it affects relationships, competition, simple consumption, greed, like, let’s hang out with those guys because they have wine there.” Financial independence made it possible to avoid disappointment from the financial repercussions in the future or not expecting welfare from one’s creative activity from the beginning. Moreover, financial independence allowed one to invest one’s own funds in projects without being disappointed with the lack of financial dividends. But such stories are more the exception in my report.

Analyzing the situation today, the majority of the central figures of this article mention the crisis, in which they find themselves, and which is associated with the conflict between the imaginary concept about an artist’s position and the actual conditions and circumstances. For example, the artist who said art opened the door for to the great world now claims this preconception was a delusion. “There was some kind of an illusive chance. As I understand now, I never saw myself leaving. I could have calmed down even earlier. But somehow I did not realize… The first door closed, then the second, the third, and here you find yourself in a compact-compact world.” Besides, he lost his passion for art, which upsets him most of all, “I realized that art is not the most important thing in life… there’s something more to it… I wasn’t going to change the circumstances, but if they had formed, then perhaps I could abandon it [art].” And yet, there are those who are optimistic despite hardships, “I believe that you can make money by making art, we just don’t know yet how… but I’m close to this discovery.” Positive responses are most common among artists of a younger age, or among those who have regular earnings in specialties close to art (translation/interpretation or pedagogical activities), or those, as they note themselves, who are in a stable situation (in harmonious relations with partners, financial stability, opportunity for frequent traveling), “You caught me in the period when I had just came back [from a trip. – Author’s note]… I had a high there.”

Parents who have not taught their children to think about the mechanisms [of the art world – Editor’s note], and that the art education in Belarus, in which the art training was “romantic nonsense… not related to reality”, often considered to be responsible for their children’s unrealistic expectations. One artist notes that she was shocked when she faced the education system at a western European art university, “It was a whole different level compared to what we had. I think there is still a huge gap. There are some advances, but not enough… there was a whole separate block of disciplines where students were taught to write applications, make portfolios… how to get grants, get to the residency”. Nevertheless, nobody is going to change something radically in his or her activity at the moment. “I can’t imagine a different way of life… I require… some kind of constant self-development and development of the community in which I exist. The important thing is the financial situation, and I manage it somehow… but I have an understanding that in my early youth I missed out on something.”

One of the reasons for frustration is the lack of a market for art in Belarus, which over the years of discussions and real actions (projects, lectures, launched websites, attempts to build a dialogue with businesses) has not developed. “On the Belarusian market, a five [$5,000 – Author’s note] is the maximum with rare exceptions. Say, artist A. received a fifty [$50,000 – Author’s note], but there was a giant canvas. All the same, fifty is nothing! This is an absolute maximum, in the next hundred years, in my view, the situation will not change… A completely open playing field, starting from zero… With my ambitions, it’s nothing.” Apart from the fact that they fail to earn money, “covering holes just for a few months”, creative activity requires constant investments. Sometimes a sold piece of work covers only the expenses for the exhibition, the organization, and the production, which fall on the shoulders of an artist. Only a few of the interviewed artists noted that the earnings from their artistic activities cover their expenses fully. Generally, they have to put themselves on a budget, to have a side job or to make money on other jobs that are far from art.

The complexity of monetization of their own work, and the constant answers to the question, “Why does it cost that much?” also affect the perception of their status, including those who work in the field of conceptual art. “The financial situation is a part of my ideology. I profess anarchism, but it is also connected to the market… I am also confused – what is art, what is not, where are the boundaries… and the market is a part of this game… Hereby you confirm this status [of an artist – Author’s note]”.

Answering the question about how much their monthly income is would then allow them to feel that they are in a more or less stable situation. On average, artists specified the amount of 2,000-3,000 BYR ($1,000-1,500), but those who have families (husband/wife, children) indicate the amount twice as large. (Here, the real monthly earnings are two-three times less, it can be the same with rare exceptions, provided there is another job in the commercial sector.) Among the answers given by the artists from Sweden about the desired income, there was a suggestion that there should be some change in the economic system and no need for money.

This is not about some extra-income from your work, but rather about the average income for Belarus, which can provide a more or less comfortable, stable standard of living (to pay the bills, to have money for leisure and education, to afford traveling, to take part in family expenses). Practically everyone noted a rather modest standard of living that they would be comfortable with, “so unspoiled… the standards are minimal… just to feel human.” At the same time, to a lesser extent they talk about stable employment, they talk more about the requirement to estimate the price of their work. Because artistic practices (especially non-financial, such as curatorial or performative) in Belarus remain free labor or a symbolically paid job, to which artists agree due to almost complete fusion of their private life (identity) and work.

Certainly, the introduction of the Decree on Social Dependency influenced the perception of the status [of an artist]. According to it, a citizen of the Republic of Belarus who has no official place of work, is not an individual entrepreneur, not registered on a parental leave, or not a member of an official art union, is obliged to pay a tax in the amount of 20 base values (at the time of writing it is 510 BYR, or 210 euros. In 2018, due to severe public criticism, the Decree was “improved” and instead of a tax, they introduced a hundred percent payment of housing and social services for those who are in the database of “dependents”. Nevertheless, the practice of differentiating citizens into “working” and “not”, the way it is interpreted by the government, is still relevant). This Decree caused artists, including those who deliberately boycotted the Unions (as a protest gesture against state and culture policy), to apply to enter those Units.5 As an alternative, a certificate on the status of a creative worker can be obtained at the Ministry of Culture: a special committee examines a portfolio of an artist (musician, singer, author) and decides on the quality of works (if the artistic level of the works matches the professional level). This certificate exempts an artist from the status of a “dependent”. “I’ve never made myself do something about it when I had to confirm my status with the Ministry… but this thing [certificate] is valid for five years. And I know, time flies away before you know it. Last year I paid [a fine. – Author’s note]. They returned it back afterwards. I got a job, provided the paper, and they returned everything.” But later the artists who stated this entered the Union, “I’m under protection at the moment. I have my work record book at one office. I teach three hours a week, but I know that I won’t last long teaching at one place, and I wouldn’t like to run around again.”

Anxiety about their current position and the future is natural for almost all the respondents. Those who are not bound by any social and emotional obligations (care for children or relatives) think about it to a lesser extent. The lack of development prospects in the conditions in Belarus (opportunities for a career), unstable income, minimal social guarantees from the state (potential lack of pensions, sick or parental leave payments) cause anxiety. Some artists, for example, are already thinking about their security for retirement: monthly deposits in a bank will subsequently provide a pension. Some of them make payments into the Social Security Fund themselves, on account of qualifying (pensionable) period. In addition to the economic reasons, the reason for anxiety is a result of modernity as a whole, when stability is impossible due to “growing old faster than one consumes knowledge. What I know today will probably be useless in five years.”

If we talk about parents’ attitudes to creative work, most respondents note that their parents are satisfied, although the positive answer is often connected with the fact that an artist has a different job. Some respondents say that their parents are worried about the unstable existence in particular (“but I managed to convince her”), some [parents] do not care or are artists themselves and thus do not know the answer to this question themselves.

The disappointment also happened due to the value-based discrepancies within the art community,6 because coming into the field of art was connected precisely to the belief “in the art sector as some exception that it should be different there. After all, people there talk so much about values, about the formation of the community, and that attracted me… Criticism of capitalism, criticism of the system. And it seemed to me that maybe that’s how we build a brave new world… at some stage I realized that something was wrong… this code of honor was not sufficiently enforced.” Many artists noted the importance of the community in interviews and in questionnaires. The community appeared (appears) to be a place of power, a guarantor of social stability and confidence, a space of recognition and receiving of symbolic capital. However, the majority relies primarily on their own efforts.

Both in the survey data and in private conversations, women artists and female culture workers noted that their non-male gender influences their work environment, both negatively and positively. Moreover, in the questionnaire, it was often indicated that “no”, it does not influence, “it’s hard to say”, “I don’t know”, “it does not influence now.” The reason for negative influence is that the way of life of a woman artist does not correspond, for example, with the traditional notion of the role of a woman, who should be a mother and a wife, and that’s why they sometimes feel psychological pressure from their relatives (parents mostly). In some cases, the existing gender scenario plays a positive role: for example, a woman artist notes that relatives “are not stressed out that much that I have to make money at a normal job and build a career.” Women artists who have children (or if they had children) note that they have to (would have to) maneuver between art/career, household and children, care is mostly on them. One answer noted a gender wage gap.

Having children drastically changed the lives of female artists (“this is the most global change in my life”), first of all they had “less time for art… There was no depression… but it seemed like I was divided into two parts…Now I understand that I just didn’t have the experience to cope with it.” The reasons for internal worries were loss of mobility (traveling opportunities, including for the purposes of an art career), anxiety associated with an unstable financial situation (“now I had to plan my future and be confident in it”), a change in relations with a partner who wasn’t included in the process of care to the extent that a woman artist had expected. Often, it was already in the process when she had to defend her boundaries and insist on the distribution of time (“Saturday is completely mine, there are a few hours on Monday and on Wednesday”).

But a child also became the impetus for the inner “discovery of oneself” and the acquisition of “fundamental knowledge.” That’s what happened to him [to a child. – Author’s note]… I’m very happy. I draw valuable insights with him… We study outer space, for example, the structure of human skin, hair layers, and this all is applicable for work!” The female artist who stated this also says that she became creatively freer that her partner, who is also an artist, because she obtained new knowledge.

Entry into the space that collapsed?

In his essay, “The Paradox of Art and Work”, curator and art historian Lars Bang Larsen (Barcelona/Copenhagen) notes the dichotomy that is common for the contemporary, primarily Western, art field, and makes a simultaneous interpretation of art as work and non-work. On the one hand, he writes that art has now more than ever been introduced into the socioeconomic sphere (“aesthetic concepts being mobilized by the labor market <…> art has been put to work like never before, and work is fixed upon art”7), and it is natural as “art is an effort embedded in cultural and social space, and, in such a way, it should be considered work.”8 On the other hand, “art is not work because it is a refusal to take part in the production and reproduction of that what exists.”9 Thus, art criticizes capitalist system, which is based on production and market relations. Moreover, being described in terms of production and labor, not differing from other human activities, art “loses its specificity.”10 For Larsen, the understanding and the movement of art in two directions (as work and non-work) is an optimal way of existence of this field – a rhythm that allows articulating other existing oppositions (state and economy, right and left, citizen and consumer, etc.).11

Such dialectics are common for the Belarusian art sphere, although its origins and manifestations have their peculiarities. If in the western context, the inclusion of art in the economic relations (for example, the emergence of a creative cluster) is associated with the capitalist system, in Belarus, the articulation of art as a production practice has its traditions connected to the Soviet ideology. Thus, Soviet official artists seemed to be a special elite class serving the ruling ideology and having financial and social privileges. They worked for the welfare of the state.12 At the same time, Soviet art and popular literature described art as the highest humanistic practice, delegating to it the solution of philosophical problems, and leaving aside, for example, the economic dimension (state orders and procurement).13

For the Belarusian art field, the romanticization of art and its interpretation as beyond the categories of work and labor are relevant today, and this is due to the traditions of Soviet unofficial art, when artists did not work and thus resisted the instructions imposed by the Soviet ideology of an artist as a culture worker. It is fair to assume that the romanticism of the Soviet underground (non-conformism) intuitively or consciously influenced the choice of life scenarios of today’s artists (“my father studied in St. Petersburg, he loved art… he had a hobby: when he was on scholarship he used to buy an album on art and a cup of coffee at a luxurious hotel in St. Petersburg… and then run out of money, and he had to load wagons…”). Often, Soviet artistic non-conformism relied on the ideas of “left” art, but, as Lola Kantor-Kazovsky notes, such identification pointed to the Western orientation of the “left” artists, who “were essentially “Westerners”, and in the “historical” Russian avant-garde, it attracted them not least of all because of the successful model of relationship between Russian art and the international art process.”14 In other words, it was primarily about the construction of an imaginary art space (including an imaginary Western one) as a combination of models of material, implications and practices,15 which undermined the dominance of the socialist discourse by creating an alternative to it. But the difference is that, if for the Western artists, not working means resisting the total market, by contrast for the Belarusian artists, it is rather a way to resist the Soviet ideologization and the politicization of art. One can see this as one of the reasons for the fact that the introduction of concept of economic productivity (culture worker, practice, labor, etc.) into the Belarusian art field is slow. As the artists of the older generation note, this dictionary seems inappropriate precisely because it refers to the Soviet past, therefore “I am not a culture worker, I am an artist!”

In recent years, the discourse on art has been changing: discussions about art as non-financial labor arise in a fragmented way (“I work a lot, but I earn little”). To a big extent, this is linked to the arrival to the Belarusian art space of a new generation of artists for whom art was not originally determined by romantic expectations, but was seen, for example, as a field for artistic research and political activities. Unlike their senior colleagues, young artists are mostly focused on the global art context, they speak about their Eastern-European identity, they speak English, study at Western institutions, actively communicate with the foreign colleagues. This allows them to freely appeal to the paradox of art in the categories in which Lars Bang Larsen describes it, placing this paradox into the focus of their art practices. A vivid example is the collective self-organized platform WORK HARD! PLAY HARD! which studies issues of knowledge production, cooperation, work, and leisure. Every year, as a part of a week-long forum (since 2016), the platform brings together several dozens of artists to discuss these topics. Despite the fact that the example of this platform is a rather unique one for the Belarusian context, it indicates certain transition processes taking place within the art sphere.

This “transition” can be associated with the changes in the sociopolitical field in general. There is a transformation of the economic regime in the country (to a capitalist form of it), which “imposes” (including for the artists) certain consumption patterns and success clichés (unlike the Soviet times, to be an artist and work as a mover, for example, is no longer considered to be prestigious). However, these changes (for now) have little or no effect on the development of the field of contemporary art in the country, which exists outside the socioeconomic sphere, practically on its outskirts, if we don’t take into account its explicit commercial formats.

The state policy in the field of culture works for the marginalization of its sphere, while the state policy is still closed for the contemporary critical practices and support for artists. Some artistic professions have not been legitimized: for example, such position as curator is absent from the register, which means that a gallery or a cultural establishment cannot officially sign an employment agreement for the position of a curator and has to look for the positions that already exist (administrator, manager, or a research associate).16 The state’s attitude to art and culture is demonstrated by a series of statements by senior officials: they often articulate the requirements, for example, to write a “big” novel or make a “big” film (a reference to the Soviet understanding of art as an ideological practice), or the bewilderment about what art produces. One of the latest statements belongs to Irina Driga, former Deputy Minister of Culture, she stated that holding exhibitions “is not an intellectual activity”, it “is not classified as a creative activity”17, and therefore it is a commercial product and is subject to the corresponding taxes. Moreover, recently the privilege of the Soviet era for health services in the special state medical committee was abolished for the culture and art workers (National and Honored Artists, Writers, etc.). This privilege remained in force for the state officials of the top rank, former party workers. The adoption of the Decree on Social Dependence also played its role in the loss of the status by artists, as it made any free artwork illegal, placing it under control (certificate issue, compulsion to form legal entities, joining unions, or labeling as a “dependent”).18

The community was viewed as one of the instruments of resistance to the state and economic ideologies. And there was a period when it seemed that this tool really worked. For example, artists from the independent art sector in Minsk recall the period from the middle-“noughties” to 2012-13, when a discursive field began to form around the pARTisan magazine and then galleries emerged: first Podzemka, then Ў. This field appeared as a community of artists, curators, philosophers, historians, whose goal was to create an art space alternative to the state cultural institutions. The symbolic culmination of this movement was the exhibition Zero Radius. Art Ontology of The 00s., which seemed to change the situation, it was viewed as an actual condition for the transition from a weak form of the discursive field (an informal get-together) to a stronger one, the creation of real self-organized institutions which could act regularly to support the members of this field acting, as an alternative political power. As Paolo Virno notes, “Institutions are the rituals we use to heal and resolve the crisis of a community.”19

For various reasons, this [transition] did not happen, and the field, which seemed as cohesive, broke down into many groups – the activities of which were aimed towards the preservation of their micro-space. Those who actively participated in the creation of that community had a feeling that it collapsed completely. “This is one of the most important things. If it used to seem that there was some common field, now everything fell apart…there is a feeling that we are in 2010. We finished the same way as we started. We thought that we were moving somewhere, everything was evolving, everything was getting better, but then poof and it all collapsed… it seemed like there were more people, the youth came… but with them it is the same as with us…” This disappointment became as well the reason for the “legalization” of artists’ labor by joining official artistic unions, “I suddenly realized that all this time I had not been learning to live here. All this time I had been living with some kind of feeling… I don’t even know were I was going to go – to the moon or somewhere else. I was wondering who would visit me – Abramovich or Saatchi, I don’t know. All the time I was thinking about something else, bollocks to the local context, and suddenly I realize that I should learn to live here. Once the decision to stay here is made.”

On the one hand, it is possible that too much was expected from that community, including what it couldn’t handle. For example, the emergence of real institutions, for which there are not enough like-minded people and desire for them to be created, but institutions also need money to function. Those artists, who initially did not bet on the local community, see the local community rather as a get-together, and “the most valuable resource for them is time.” These artists point out their integration into the global art field (primarily due to their knowledge of the English language), gain recognition at international festivals, while actively participating in local projects. The lack of internal resources in the art field within the country for them is a part of an overall picture, and one community is not enough to change it. On a smaller scale, the resources works to create micro-movements (a vivid example is the “barn” exhibitions by artist Olga Maslovskaya in Brest), but for radical changes we need “radical changes within the country.”

On the other hand, the “collapse” of that community may signal a rethinking of the concept [of the community] itself, it began to be viewed in plural form. As Belarusian philosopher Olga Shparaga notes, the most important concept for the contemporary artistic practices is to create the conditions for the emergence of a situational community, the one that marks out situations here and now, sharpens the attention and brings the invisible into the light.20 Such community is also formed on the basis of solidarity, but has time limits. It can be assumed that exactly this kind of a situational community arose in the Belarusian art field at the moment of political and economic upheavals and marked the “transition” (or its prerequisites) to more diverse forms of these communities, “for which there are determinant factors such as the value and the practices of horizontal mutually respectful relations of the members of the communities, as well as the social inclusion based on those relations.”21 However, as the philosopher points out, to strengthen a community like that, it is also “important to search for forms of their adequate institutionalization,”22 which requires political will and support from above, at least at the level of the right to communities, which is difficult to imagine in the situation of modern Belarus.

Thus, despite the existing range of local peculiarities related to the sociopolitical situation and cultural traditions, the processes of rethinking of the art field and the role of an artist in the Belarusian context are synchronized in a lot of ways with the processes occurring in the Western discourse. In addition to the common causes for anxiety and vulnerability that has to do with how success within work is constructed and the subsequent lack of social security; artists in Belarus also articulate the fusion of personal and artistic identities, realizing that their work involves a high level of emotional inclusion and production through social communication (“it is not the work that you go to, it is something as close as possible to yourself… it is odd to imagine doing the work without getting involved with my entire soul”). Unlike the Western context, where unalienated, or using the terminology of Hardt and Negri, biopolitical labor is actively exploited and appropriated by the capitalist system, in Belarus this labor is mostly required within the art communities or sociopolitical organizations that have the funds, for example, to maintain their infrastructure, but with limited budgets and rare opportunities for royalties for artists.

At the same time, there comes an understanding of the exclusiveness of their position in the modern world, where unalienated labour becomes a luxury. As Alexandra Novozhenova, a Russian fine art expert and artist, noted, “to be an artist is the option, which (not without compensation) is presented by the society to those who cannot find the strength to retreat to other activities… the oppressed are those who have no power over their own lives, and entering an art school seems to be a way to get your life back.”23 Those artists in Belarus who remain in the art field, like their Western colleagues, say that in some way their anxiety is the price for the returned life, the example of which is a form of resistance and an attempt to implement another life scenario.

-

As well as male and female culture workers (curators, art managers, critics), but further in the text I will be using the term artist to rather stand in for a concept of a culture worker, which has been hardy articulated within the art environment.↩

-

An online questionnaire was distributed personally and posted in a special private group on Facebook. 38 people from the age of 25 to 60 took part in the questionnaire, and most of them specified their sex as female. Work experience in the field was specified from 4 to 35 years. Geographic location (original answers): Minsk, Mensk, Brest, Bobruysk, Minsk/Vienna, Minsk/Warsaw, Belarus, Planet Earth. Artists from Russia and Sweden also participated in the questionnaire, their experience is used for comparative analysis.↩

-

The space for art in Belarusian is a diverse field, where many people from different sectors, such as the state and private sector communicate together, and private and collective initiatives are present. A detailed description of this field deserves a separate research. That’s why I’d like to note the formality of usage of term “independent” necessary for the simplification of narration. Moreover, this research fragmentarily gasps this field, analyzing the experience of one of the segments. ↩

-

The said stories of “success” are stories of male artists.↩

-

They mention entering into the Belarusian Union of Artists or the Belarusian Union of Designers as a variation.↩

-

By art community here we mean a field which was formed in an alternative art sector in the “noughties” around the pARTisan magazine, gallery Podzemka, and then gallery Ў. Within this field, a series of projects and initiatives have been realized for years, e.g. project On the Way to Contemporary Museum by Alla Vaysband, mediaproject Zero Radius. Art Ontology of The 00s. by pARTisan and Art Aktivist and many other projects. It’s important to note that the analysis and the description of this community requires a separate research.↩

-

Larsen, Lars Bang. “The Paradox of Art and Work: An Irritating Note.” In Work, Work, Work. A Reader on art and labour. Sternberg Press, 2012. p.19.↩

-

Ibid, 21.↩

-

Ibid, 23.↩

-

Ibid.↩

-

Ibid, 27.↩

-

The Soviet art field was not homogeneous. Thus, for example, K. Solovyov describes several strategies of artistic and intellectual activity: e.g., “ideologist-fundamentalist”, “careerist-functionary”, “neutral objector”, “independent specialists”, “dissentients”. See K. Solovyov, Artistic Culture and Power in the Post-Stalin Russia: Union and Fight (1953-1985). Nevertheless, the rhetoric of art unions, membership in which was necessary at least to have a studio, access to art materials and an opportunity for display, emphasized the labor character of a Soviet artist’s activity, opposing it to the bourgeois lifestyle, e.g. of modernist artists.↩

-

In recent years, there’s more and more material – memoirs, publications, and books – where practices of privileges and the consumption of culture elite in the USSR are described. But in the Soviet era, this side of life was invisible in the public discourse supporting rather an image of artists’ activity as the most important element of socialism development.↩

-

Kantor-Kazovsky, L. Grobman. New Literary Review, 2014. P. 14.↩

-

Gapova, Elena. “’The Land Under the White Wings’: the Romantic Landscaping of Socialist Belarus.” In Rethinking Marxism, V. 29(1). Pp. 173-198. The concept of an “imaginary landscape” Elena Gapova uses to describe the emergence of a new class in the Soviet Belarus, writers intellectuals who created an alternative image of Belarus as a “country of castles.” In my opinion, this concept is also applicable for comprehension of other imaginary spaces that emerged in the

Ssoviet art circles.↩

-

See State Professions Register: https://otb.by/polezno/okrb.↩

-

Ministry of Culture: holding exhibitions is not a creative work. TUT.BY, January 2, 2019. See https://news.tut.by/culture/621269.html. Accessed February 11, 2019.↩

-

Penzin, Alexei. “The Soviets of the Multitude: On Collectivity and Collective Work: An Interview with Paolo Virno.” In Mediations 25.1 (Fall 2010) 81-92. See www.mediationsjournal.org/articles/the-soviets-of-the-multitude. Accessed January 24, 2019.↩

-

Shparaga, O. Community-after-Holocaust. On the Way to the Inclusion Society. Medisont, 2018. Pp. 316-317.↩

-

Ibid, 29.↩

-

Ibid, 234.↩

-

Novozhenova, Alexandra. School Art. Colta, February 12, 2014. See https://www.colta.ru/articles/art/2020-shkolnoe-iskusstvo. Accessed February 7, 2019.↩