In the summer and autumn of 2020, “The Square of Changes” was perhaps the most famous place in the rebellious Minsk geography. At first glance, it is by no means a remarkable patch of land with a modest playground and a gray transformer booth, which suddenly became the epicenter of a series of dramatic events: from spontaneous acts of solidarity and unconditional support, to tragedies that led to the death of a young activist and ruined the lives of anyone who stood against the regime.

Photographer Yauhen Attsetski has a direct connection to the people’s “square” that was named after one of the informal hymns of the protest 2020 – a Viktor Tsoi’s1 song “Changes!”. Living in one of the high-rises nearby, he was fast to realize its historical potential for the annals of the last presidential elections and started his photo project. In his case, however, the neighbor’s perspective gradually transformed into that of an observer with a camera, and later – into an archivist of the history that Lukashenko’s regime would try hard to erase from collective memory. Two years later, Yauhen’s images would be seen by 3 million readers of The New York Times, and it would take his team only a fortnight to raise more than 12,000 USD for the publication of the photobook about neighborhood protests demanding change.

In a special interview for the Status Platform, Yauhen Attsetski speaks about a difficult journey from the Tsentralny District Police Department of Minsk, where he ended up after being arrested at a rally, to the Ukrainian town of Lviv, where he is now based with his family in exile. After a search conducted by the KGB, he packed his entire life in several suitcases and in the midst of war, the photographer nevertheless continues doing his job: resisting Lukashenko’s regime to destroy the collective memory of Belarusians and finding reasons to be proud of his people and their struggle for a better future.

Yauhen Attsetski

Belarusian photographer, citizen journalist. Works mainly in documentary photography. Collaborated with the UNDP, UNICEF, Red Cross. His photos and photo series were published in The New York Times, Sapiens, TIMER, Kultprosvet, etc. ‘He has participated in numerous exhibitions in Belarus and abroad. In 2021, facing political repressions, he moved to Kyiv, and with the outbreak of war – to Lviv, where he is still based.

https://squareofchanges.net/

31.08.2020

– I got involved in the political life of Belarus back in 2006 and 2010 when the presidential elections were held, both times ending in a violent suppression of street rallies. Since then, my hope for the country’s different future has been fluctuating: fading with the outbreak of the war in Ukraine in 2015, and strengthening with the “parasites” marches in 20172, but never could I think where and with what thoughts I would enter 2021.

Initially, I was fairly neutral about the 2020 election campaign, but the queues for collecting signatures for alternative candidates at the polling stations quickly brought me back to my senses. It became clear that something very interesting was about to start. So, in May I grabbed my camera and went out to the city – and it was on the streets, documenting the unfolding events, where I remained for almost a year.

Often it is not you who bumps into a story, but a story that bumps into you. After the events of August 9, 20203, Belarus was in a state of shock. It became obvious: the elections had been rigged, and police clubs beat the desired result into people’s heads. However, too many civilians found themselves under the pressure of violence and faced repression, and the strategies of consequence-free aggression successfully tested in the previous elections this time did not work.

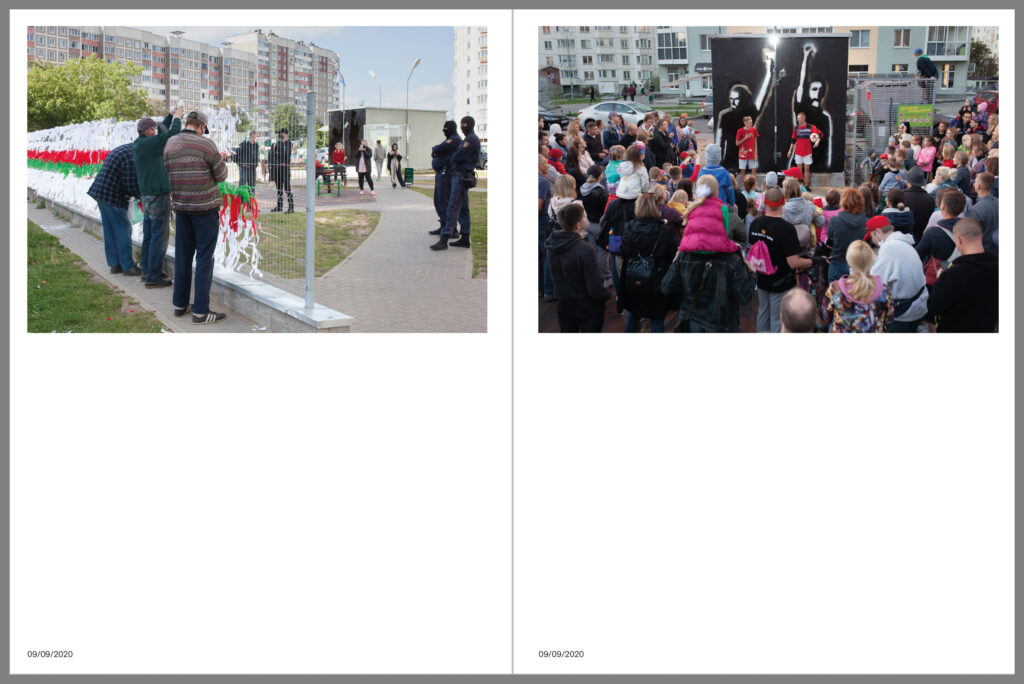

On August 11, I heard some noises coming from the backyard and saw my neighbors shining flashlights from their windows and chanting political slogans – actions for an ordinary Minsk neighborhood rather unusual, if not to say “out of the ordinary”. I remember shooting my first video that evening – a reel that later would become part of my project. Further events unfolded very rapidly: the appearance of a mural featuring the opposition DJs on “the Square of Changes”, its endless destruction and restoration, the death of Roman Bondarenko murdered by plainclothes police, Stepan Latypov’s4 arrest. As a documentary photographer, I recorded everything, realizing the extreme importance of not leaving any moment out of my sight.

After the start of the election campaign in Belarus, I always carried my camera around. Almost every day I shot political campaigns and actions held in the city or in my backyard. Finding a common language with my neighbors took some time – initially, they treated me with caution, as they usually do when spotting a man with a camera. Switching between two impulses (the roles of a neighbor and a photojournalist) was not easy, I should admit. The internal conflict was resolved when I realized that the government began to openly break the law. It was then when I made a decision, and my involvement in shooting ceased to be a hindrance, as I began to define my work as citizen journalism. I keep an eye on the documentary element, but at the same time I do not hide my political views and attitudes to what happens in the country.

While shooting, I constantly ran into policemen and tikhars5, and these encounters often ended in verbal disputes. It was difficult to hold back, seeing my neighbors under attack or symbols and objects important for our community destroyed. During the debates, I tried to address policemen not as functions and performers, but as citizens of the Republic of Belarus. I requested them to explain their behavior and asked them if they really wanted to live in such a country and whether they considered what was happening to be normal? These conversations were based on my assumption that doubt could provoke change – and to make tikhars question the adequacy of their actions was what I really wanted to achieve.

In November, after being detained on a Sunday march, I ended up at the Tsentralny District Police Department, where I unexpectedly saw patrolmen and tikhars from our yard. Despite the fact that all of them were either in balaclavas or masked, we recognized one another. I felt a bit uncomfortable finding myself on their “territory” this time. Also, among those working there that evening, there was one man who did not hide his face. Taking me aside, he said, “If I see you in that backyard again, you will pay all your neighbors’ fines!” His face is what I still remember well.

November 15, 2020 – the day of the attack on the “Square of Changes” – became the culmination of my backyard’s story, which made me seriously reconsider the form of my future project. I sent a proposal to create a photobook with a Swiss designer to Pro Helvetia and was selected. The work was carried out in a team: Melina Wilson helped us with the design, and the editor Alesya Pesenka – with the texts. In addition to photojournalistic storytelling, we decided to focus on eyewitnesses’ accounts and already then (in early 2021) I began collecting materials and shooting the portraits of the protagonists.

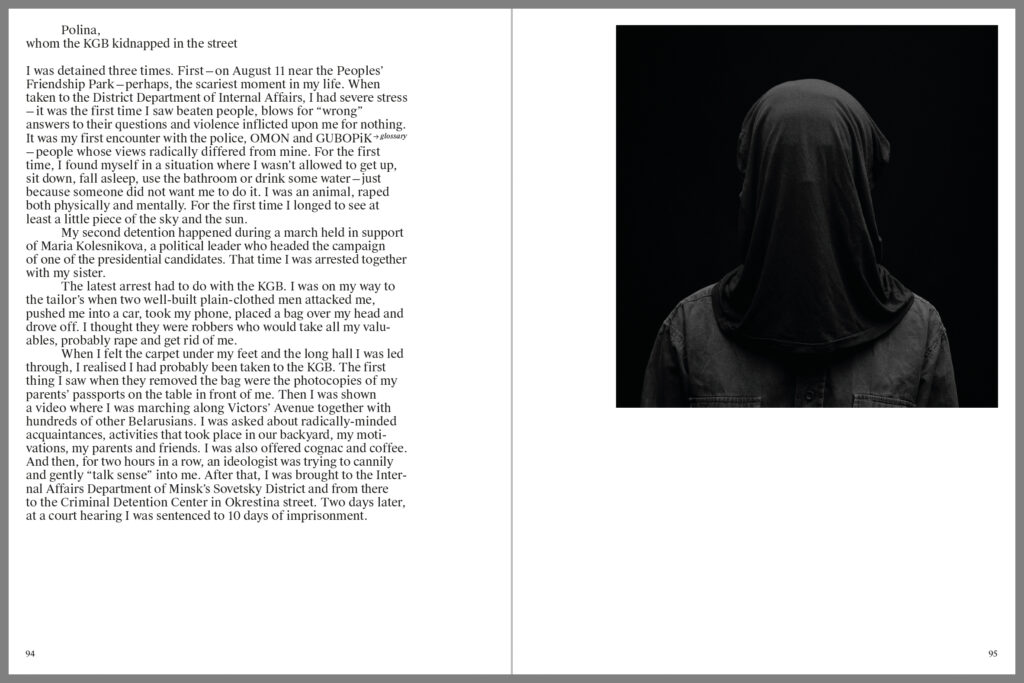

Since I immediately saw the project as a composite, consisting of exhibitions, a website and a photobook, I also approached shooting portraits in a complex manner. At first, I was planning to photograph all the participants with their faces in the open and hidden, thinking I could use the open variants, in color, in the book, and the closed ones, black and white, on the site. However, observing the repressions only growing in scale, I soon realized that the time to reveal my protagonists’ identities had not yet come.

But the materials I was collecting included not only photojournalistic documentation and interviews – to get a wider picture I also addressed my neighbors asking them to share mobile snapshots and videos of the main events that had occurred on “the Square of Changes”. This archive made it possible for me to almost completely restore the timeline of the mural’s creation and destruction. It turned out that the image of “the DJs of Changes” appeared on the wall more than 20 times.

I am very glad to have managed to collect my neighbors’ stories at the beginning of 2021, when the residents of “the Square of Changes” were still full of hope and shared their experiences very sincerely. Now, after almost two years of terror, people are extremely careful about being vocal and are very much prone to self-censorship. Fear seems to have consumed the whole country and its people. Today, making such emotional interviews would be impossible.

The goal of our project is not to let history be rewritten. In one of his speeches, Lukashenko said that he did not mind “turning over a new leaf”, which implied that he wanted to forget the events of 2020 and continue living “as before”. However, turning the page with one hand, the authorities use the other one to impose the regime of political terror, closing all the NGOs, all educational and cultural initiatives, liquidating independent media and giving unthinkably harsh prison sentences for any manifestation of dissent. My team and I, like many other Belarusians, consider it unacceptable to turn a blind eye to what is happening, and the project represents our attempt to remember and document the events of 2020-2021.

I see a photobook as an ideal form of such documentation because the book itself is a physical object that one cannot so easily cancel from the material world. In our case, the texts will be in two languages – in English and Belarusian, which we believe to be important. In 2022, after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, it became clear that confronting the eastern neighbor, with its imperial ambitions and a pronounced resentment, is a central goal of the entire region, and here language becomes one of the tools to distance ourselves.

In addition to the release of the photobook, we are planning to launch a site in four languages: in Belarusian, English, Russian and Polish. We have held more than 10 exhibitions across Europe. The most expressive, by the way, was the exhibition in Riga, where the festival’s organizers built a full-scale mock-up of the booth from “the Square of Changes” with a flag, a mural with “the DJs” and my photographs.

When working on the project, for the first time in my life, I also played an art manager’s role. As a manager, I had to deal with correspondence and meetings, fundraising, and accounting (searching for ways to finance my team’s salaries). Many of the team members (most of them are Belarusians, but there are also guys from Switzerland and Ukraine) were ready to work at reduced rates, some – for free. However, I believe that paying decent salaries to culture workers is extremely important, so I did my best to find ways to reward them for their input, which was not always easy… We addressed various organizations, called up embassies’ representatives, but many of our applications were never answered… I clearly felt the art world’s bureaucracy. Understanding that I did not want to change my project to fit every grant, I suggested organizing a crowdfunding campaign and reaching out to the community.

We managed to collect the requested amount in about a fortnight. We received a lot of orders from Poland and the USA – countries with strong Belarusian diasporas. Of course, I would really like the book to end up in the homes of Belarusians in our homeland, but so far, unfortunately, it is too dangerous. Ordering books from Belarus is possible, but delivery there is still questionable.

So far, we have received orders from 33 countries, and we also would like to send copies out to libraries. In April 2022, the issue of The New York Times came out with my photo on the cover – more than 3 million readers got acquainted with a story of our yard. I am very glad that so many people learnt about the events taking place in an ordinary Minsk backyard. This prevents Lukashenko’s regime from just turning over a new leaf. My neighbors were arrested and beaten, searches were carried out in their apartments, some are still in prison, many were forced to leave the country. How can you turn a blind eye to this and pretend that nothing happened? The Belarusians have demanded and are continuing to demand justice.

In July 2021, the KGB came to my wife with a search warrant (fortunately, she was not at home). This episode forced us to pack up and leave Belarus, and Kyiv became our new home – but not for long. On February 24, Yulia woke me up showing a video of Russian tanks entering Ukraine through the Belarusian border. This pushed us on the road again, and a few days later we arrived in Lviv. Of course, the war greatly unsettled me, but I managed to pull myself together and continued working on the project. The final variant of the photobook was sent to the printing house from Ukraine – the most important place in our region at this historical moment.

12.11.2020

12.09.2020

One day, on a bus I met a woman from Kharkiv. The trip was long, and we had enough time to discuss a lot of different topics: from politics and her life in Kharkiv to the former Khirkov governor Dobkin and “Ahnenerbe” research society, founded in 1935 by Himmler in order to search for artifacts of the ancient power of the German race. Like many Ukrainians who I had a chance to communicate with here, the woman was fascinated by Lukashenko’s animal-like resourcefulness, in which I often saw a reflection of a certain internal conflict. On the one hand, people in Ukraine hate Lukashenko for letting Russian tanks into the country, and on the other hand, they cannot but recognize his vitality and cunning.

To help my travel companion better imagine what many Belarusians had gone through in 2020, I showed her a still unfinished site about “the Square of Changes”, where one of the videos clearly showed hundreds of people gathered to honor the memory of the murdered artist Roman Bondarenko. After watching the fragment, she exclaimed, “And did it really happen in Minsk??”

I have been living in Ukraine for a year, having numerous contacts with the locals and I understand that many people have a very vague idea of the events in Belarus in 2020-2021. Most often, they admit to having actively followed the very start of the protests, then their interest faded, and later they only saw the headlines of individual tragedies, such as a plane landing with Roman Protasevich. And such a reaction seems natural to me: the Belarusians showed the same level of interest in the Maidan in 2013-2014. Unfortunately, the Belarusians and Ukrainians still know each other very poorly and do not always understand the peculiarities of the contexts. If I manage to stay in Ukraine (the Belarusians are now facing a lot of difficulties with legalization), I would like to do joint projects with local cultural figures. I am sure that something interesting might be born out of the dialogue between these two cultures, and we will begin to better understand our peoples.

An example page of the book The Square of Changes

An example page of the book The Square of Changes

An example page of the book The Square of Changes

- Viktor Tsoi was a Soviet singer and songwriter of Korean-Russian origin who co-founded “Kino” – one of the most popular and musically influential bands in the history of Russian-language rock music.↩

- A series of peaceful rallies held in 2017 in Minsk and a number of reginal centers in Belarus as people’s spontaneous reaction to a tax levied against the unemployed (or “parasites”, as Lukashenko would define them).↩

- Belarus security forces viciously beat and detained protesters over the country’s presidential election outcome on August 9 and 10, 2020. The security forces used stun grenades, rubber bullets and slugs, blanks from Kalashnikov-type rifles, and tear gas against demostrators who gathered in Minsk and a few other Belarusian cities to protest the official election results, which were largely recognized as rigged. See, for example, here https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/08/11/belarus-violence-abuse-response-election-protests↩

- One of the most famous “Square of Change” residents, an arborist who was attacked and heavily beated by plainclothes police force members in his own yard and later sentenced to 8.5 years of prison for giving flowers to female protestors in Augist 2020 in Minsk. During the trail Stepan tried to commit suicide with his last words being “”GUBOP [the most infamous police unit in Belarus] promised that if I don’t plead guilty, there will be criminal cases against my relatives and neighbours”.↩

- Plainclothes policemen on duty↩