0

Work is always repressive. It ties to a place and imposes more or less stable relationships of subordination, discipline, and power. There is only one record of official employment in my employment book: at the age of 17 I had a construction job for a month. The path of my academic education – undergraduate, first and second masters programs – happened to be sufficient enough to form a certain zone autonomous from work, creating space for self-education, interesting personal projects, and leisure. However, freelance work in the cultural field of Belarus is an area of refined exploitation: be it writing an article for 30 euros, organizing a large collective exhibition with commissioned works for 1200 euros and a festival for 180 US dollars, or free editing, psychological help and counseling for artists.

Introduction of a new parasite tax in 2015 became a certain threshold. A coercion to work was added to the habitual exploitation in the background: a disciplinary hand, which forces to seek employment and takes money out of your pocket if you refuse to work, has returned. This hand delicately looks after the cultural workers, the ill, the broke, and the anarchists. It brings forms of control, unusual for developed capitalism, including tax office card indexes, postal notices, detentions, fines and, finally, police violence against people who disagree with the law. Naturally, the power of a rubber baton is adjacent to and intertwined with the self-discipline, the micro-policies of power, and the economic mechanisms of a society of a developing authoritarian capitalism.

1. EASTERN EUROPEAN LAZINESS AND COERCION TO LABOR

In an important text In Praise of Laziness, unfinished due to his own laziness, Croatian artist Mladen Stilinović writes: “Laziness is the absence of movement and thought, dumb time — total amnesia. It is also indifference, staring at nothing, non-activity, impotence. It is sheer stupidity, a time of pain, of futile concentration. Those virtues of laziness are important factors in art. Knowing about laziness is not enough, it must be practiced and perfected.” Learning from capitalism and socialism, Stilinović says that there is no more art in the West – only competition, production of objects, gallery structures, and hierarchies. The East (Eastern Europe) in its turn has always maintained a gap, in which an artist could practice beyond the market or expertise. This text does not aestheticize or essentialize laziness but rather characterizes the place of art in the system of late socialism and during the transition period, pointing out the instability of its forms, the lack of equivalence and the formalization of economic relations. The place of art is the place of boiler rooms and watchposts, which were occupied by intellectuals in order to free space for art and research – which then, however, wouldn’t be converted into economic capital. It is a counterproductive power of work. These “low” workplaces were important as an element of resistance to the coercion to labor, as an attempt to bypass ideological rituals and to wrest hours of free time from state-sanctioned “socially useful labor”. The law on compulsory employment “On Strengthening the Fight against Persons (Loafers, Parasites) who Avoid Community Work and Lead an Antisocial Parasitic Lifestyle”, adopted in 1961, primarily fulfilled the function of ideological control and in the 1980s led to the formation of various practices of subversion and evasion from the coercion to work.

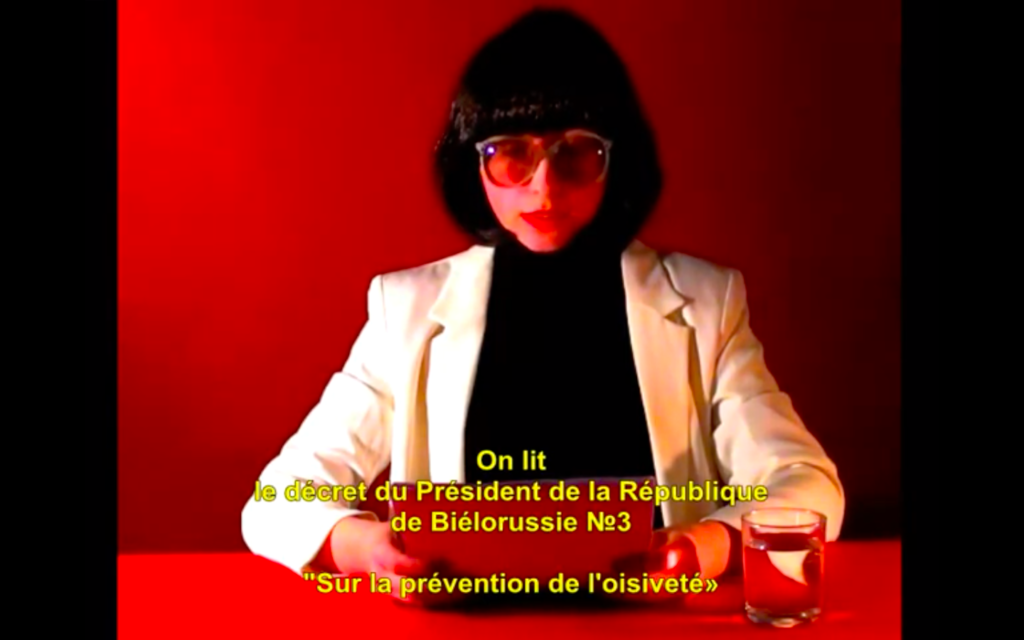

With the fall of the Soviet Union, the coercion to labor was internalized: work became necessary for not dying from hunger and poverty. There became even less laziness with the arrival of Western funds. The necessity to understand the operational mechanisms of a Western cultural field arose: how to build a career, receive recognition, and work on projects. On April 2, 2015, Decree No. 3 of the President of the Republic of Belarus on imposing a parasitism tax (Decree on the Prevention of Social Dependency) came into force in Belarus. The Decree obligates citizens who have been unemployed for 183 days to pay a tax of 20 base values1 during the calendar year (in the Spring of 2020 it was about 205 euros). In fact, an old form of the coercion to labor but in a new ideological shell and with new modes of economic exploitation, has returned to its place.

Despite the fact that the questions of labor and laziness of an artist has always been considered essential in the art of Eastern Europe, in Belarus, for a number of reasons, this topic is only beginning to play such an important role. It is further complicated by the economic conditions, including the absence of a law on freelance, the criminalization of foreign financing, the inarticulate status of cultural work, the lack of education and private capital in the field of art.

In the case of Belarus in the 2010s, this Decree was initially adopted in an attempt to find money for the budget during the economic crisis. It was primarily aimed at Belarusians working abroad and not paying taxes in the country but in an unexpected way the directive shed new light on the socially unprotected types of labor: the labor of a mother-housewife, the inexpensive labor of an artist, and the labor of a freelance journalist. In fact, the Decree became a powerful monitoring tool, which also showed the complete erosion of the concept of “social state”, which is so actively used in Lukashenka’s Belarus. This was a kind of authoritarian measure of extreme economy: the financing of social sphere was not just cut as in neoliberal capitalism but was pulled out of the hands of the sick, the disabled, and the anarchists, disciplining everyone else and completely wrecking social state and its fundamental social democratic idea of social security: if you want to get “free” education and healthcare — work! The only difference is that with the introduction of this Decree, control is exercised not so much through the level of ideology as through the economy: if you don’t want to obey – pay!

Against the backdrop of an extremely difficult economic situation, the Decree (the enforcement of which began a year later with the start of a new tax cycle) provoked one of the most powerful waves of civil protests unaffiliated with the official political parties or movements. At first, the protests were held without any intervention from the government but from the beginning of March, riot police began to detain and disperse. On March 15, an authorized march against the Decree took place in Minsk, after which riot policemen in plain clothes detained anarchists and other passengers traveling from the rally by public transport. All of them, induced by the perjury of riot police, were sentenced to administrative arrest for a term of 12 to 15 days. On March 24, the number of detainees exceeded 300 people, and dozens of those were fined. The demonstration on March 25 was in fact blocked by the authorities: city transport did not stop in this part of the city, police and riot police detained almost all passers-bys, and the column of anarchists was seized as they were approaching the venue.

The exhibition of Maxim Sarychev “Blind Spot”, which took place shortly before these events inside the Minsk exhibition space CECH, was dedicated precisely to this topic. Powerlessness in face of the police apparatus, fear and paranoia in face of a possible search and detention, psychological and physical violence were metaphorically conveyed through gloomy images of billboards mangled in the 2016 storm, disturbing landscapes and pits, illustrations depicting body parts most vulnerable for striking blows. It is not surprising that the activist depicted in one of the portraits of the series ended up behind the bars again.

2. FREELANCE AND THE UNION OF ARTISTS

In an interview with a German artist Hito Steyerl, Oleg Fonaryov, a Ukrainian developer and programmer, gives an example of transformation of the global economic ties, using the concept of “nearshore” as opposed to the concept of “offshore”. In the field of information technology, the countries of Eastern Europe began to appear as the source of outsourced labor – competent, high-tech, and cheap. It is not surprising that in the close proximity to the real combat actions, virtual military simulations, computer games, and 3D graphics are being created. This is characteristic of one of the several trends that determine the Eastern European regimes of labor and leisure. If the work of a programmer pulls the average salary level to its high horizon, then the work of a cultural worker remains at its lower horizon.

For example, the work of a librarian is considered one of the lowest paid with the full rate of 160 euros, including bonuses, (as of the summer 2017). The introduction of the decree on parasitism became a catalyst for discussions about labor and the status of the artistic labor specifically: how it can be determined, paid, and defended.

While the decree on preventing social dependency in Belarus primarily focuses on “black” economic activity, it is in the cultural sphere that its ideological effects are revealed.

How can an artist avoid paying parasitism tax?

One could become a freelancer, obtain the status of a creative worker, organize a fictitious sect, combine art practice with official employment, become a member of the state-controlled union of artists, designers, or architects; study abroad, obtain a disability certificate, move to the countryside and get permission from a kolkhoz to cultivate the land, become a craftsperson.

All of these forms of tax evasion are widely practiced and discussed in the artistic field. Since the average income of an artist is extremely low and there is no more or less reasonable legislation on freelance, combining several jobs (programmer and photographer, designer and artist) remains the most common solution.

In Belarus, the official policy of the Ministry of Culture foremost recognizes structures that have not fundamentally changed since the Soviet era: for example, the Union of Artists or the Academy of Arts. Obviously, in many ways this is done to maintain a high level of ideological control. At the same time, private corporations or enterprises construсted with oligarchic money began to actively earn symbolic capital, such as the projects of Belgazprombank (a subsidiary of Gazprom) or Dom Kartin (The House of Paintings – the project of the runaway Ukrainian oligarch Igor Yakubovich). These intersections give rise to the hybrid institutional forms combining bureaucratic management, private capital, and ideological censorship. All official members of the unions of artists, designers, and architects are exempt from tax, which highlights a top-down way of managing culture.

Freelance artists, designers and photographers remain outside of the legal framework of the parasitism tax. Despite the fact that there are legalization methods (for example, through registration of individual entrepreneurship), many of them remain predatory in practice.

For those who are not members of official unions (in order to become a member of the Union of Artists it is necessary to obtain a higher art education in one of the Belarusian institutions and participate in republican exhibitions), there is an option of submitting an application for consideration of assigning the status of a creative worker. The committee deciding whether the applicant is a creative worker includes all the same bureaucrats and the heads of the official unions. The commission is headed by the First Deputy Minister of Culture. As a result, there are cases when electronic musicians do not receive a certificate due to their lack of knowledge of scores and notations; artists’ painting may be considered too abstract or insufficiently academic; an applicant lacks recommendations and references in the state press.

Today the Decree has just been put on hold for a year and no one knows what the next spring will bring: protests and grassroots cooperation movements, a real union of cultural workers, new forms of cooperation? Or, as it often happens, silence, apathy, locking oneself in the studios and workshops?

3. COMMUNITIES, FICTITIOUS RELIGIONS, PRODUCTION DRAMA

It is hard to tell that in the history of Belarusian art artists have often questioned changes in labor structures, working conditions within their field, or economic issues. In the 2000s Marina Naprushkina was in a dialogue with city planners and architects, Alexander Komarov compared the operation of Siberian mines to the Frankfurt stock exchange, Bergamot group threw coins at a gallery owner during a performance and tried to determine the status of an artist. The younger generation of artists began to directly criticize the conditions of their work: artistic routine and common problems of Eastern European art, such as the lack of exhibition spaces, corruption, nepotism, and the conservatism of the art mainstream. The examples include actionism and the trial against the National Center for Contemporary Arts by Aliaxey Talstou, photo montages depicting fictitious closure of all art-related venues in Minsk by Sergey Shabohin and his series of illegal lectures for the students of the Belarusian State Academy of Arts, an exhibition Diploma which criticized the system of art education, the work of Zhanna Gladko in which she researches unprotected and invisible care labor of an artist and the hierarchy within the art system.

The eeefff group composed of Dzina Zhuk and Nikolai Spesivtsev from the very inception of its practice was interested in how labor is transforming within its contemporary digital non-material state, in how the automation of labor functions, in the contact between its human and non-human sides, interfaces, algorithms. The eeefff is a part of Work Hard! Play Hard!, as well as of Flying Cooperation – projects that offered a new look at the relationship between labor and leisure after the introduction of the parasitism tax.

The series of events Work Hard! Play Hard! was developed to reflect on labor and leisure experience, productivity and laziness, intensification, amalgamation, and interpenetration of different labor regimes. The working group (Dzina Zhuk, Nikolay Spesivtsev, Olia Sosnovskaya, Aleksei Borisionok) was interested in not only the questions of working conditions of artists and curators, but also in the disposition of labor in general. The project and the invitation to participate placed greater focus on changes in this configuration, on operational models of a classic factory and a corporation, which are draining resources from the earth (for example, Belaruskali), on ways in which a new type of economy extracts emotional and cognitive capacities – be it outsourced work of a programmer, exhausting activist labor, woman’s reproductive labor, or leisure time of a raver, a philosopher, or a factory worker. WH!PH! is first and foremost an attempt to invent a space in which these subjects can be discussed in different discursive and performative formats, not only within the framework of a narrow local cultural field, but from a broader Eastern European perspective; a space where it is possible to invite friends and colleagues to create an event which is powerful and charged with the affect of co-participation.

In 2016, WH!PH! was dedicated to mapping concepts related to the culture of late capitalism, affects of labor and leisure: laziness, hedonism, over-productivity, fatigue, psychological stress. In 2016, a group of artists Flying Cooperation began to develop a draft of a project intended to help in deferring from the parasitism tax. Upon careful reading of the text of the Decree, the group found out that “priests, clergymen of a religious organization, members (inhabitants) of the monastery, monastic community” are exempted from the tax. This line of the Decree prompted the development of the fictitious cult Exocoid: to form a cult associated with a flying fish, a fake sect was created with its own history, rituals, places of worship and protocols. Within the framework of the exhibition Politics of Fragility in the gallery on Shabolovka (Moscow), Flying Cooperation invited visitors to become parishioners. The documents supporting the establishment of the fictitious cult were submitted to the tax office, but most likely have not been considered due to the suspension of the Decree. The foundation of a cult in this case is not a new-age, spiritualistic practice, but rather a new grassroot form of cooperation and self-organization (which is one of the main conceptual horizons of the FC), as well as a creation of new systems of kinship and friendship.

In an interesting way, the quasi-religious form of response to the parasitism tax, also combining the perestroika context of post-Soviet quasi-mystical cults and the black economy (financial pyramids, ‘charged’ drinking water), was suggested by Daria Danilovich. In a series of videos, on behalf of the fictitious organization Mezhdunarodnyi (“International”), the artist is ‘charging’ water with ‘psychic energy’ so it could be consumed for healing or protecting oneself from paying the tax. She introduced a new economic barter system, which aims to criticize the formality of the number of days – 183 a year – that must be worked off for dodging the parasite tax.

In 2017, with the help of an abstract machine of “transmission” – “an imaginary tool for controlling acceleration, which involves the contact of gears: bodies, objects, stories and affects” – WH!PH! called to pay attention to the processes developing at different speeds and at their collective work, intersections and breakdowns. The term “extractive capitalism”, which a researcher Saskia Sassen explores in her 2014 anthropological poem “Expulsions”, explains how modern capitalism works and brings under a common denominator the various processes of profit from the earth and from the body. The new phase of capitalism, which is no longer exclusively related to the modernist productivity, mass consumption, and the circulation of goods, is rather a gigantic mechanism for extracting value from humanity and nature, with the gradual exhaustion of all possible resources, including mental and cognitive abilities as well as the biosphere.

For instance, Uladzimir Hramovich brought up the case of the Belaruskali corporation and the city of Soligorsk, built for the production of potassium – the basis for the prosperity of the Republic of Belarus: billions tons of potassium were unearthed in 2003. Using it as a rhetorical example, the artist suggests filling these newly formed cavities with art to serve as corporate collections (an example of the latter is the collection of another corporation – Belgazprombank). Furthermore, as part of WH!PH! body was discussed as a different exhausted cavity filled with affect: in conversations on emotional work with Ira Kudrya and emotional burnout with Tanya Setsko.

Lina Medvedeva and Maxim Karpitsky organized a screening of the Belarusian Soviet film of the early 1980s His Vacation, the plot of which revolves around a shock worker Korablev who establishes that the the poor quality of details sourced by the subcontractors is the cause of constant production problems. Korablev takes a vacation, travels to another city to the Krasny Lug factory and gets a job, while hiding the true motive of his arrival. He is going to readjust equipment in the factory workshop where the details for his home factory are produced.

The film genre can be described as “production drama” and beyond the framework of the Soviet genre cinema, it seems to me that this term can describe many of those surfaces that are being deformed under the influence of extractive capitalism. In general, I would suggest considering these artistic reactions to parasitism tax as a kind of production drama which exposes and analyzes not only the industrial labor itself, but also how mental, emotional and cognitive competencies become a part of what was called the extractive machine of capitalism in the conditions of authoritarianism in Belarus.

*This essay was originally published in Hjärnstorm nummer 132: Belarus/Sverige in 2018 and edited for the publication on Status Platform in July 2020.

-

The base value in Belarus was established in 2002 instead of the minimum wage. It is an indicator of the calculation by the Belarusian government of the size of pensions, benefits, taxes, fees, and penalties. ↩