According to numerous critics of the protest movement, none of the protesters in Belarus are doing it right. Frustrated by the fact that the protest has not immediately resulted in the regime’s fall, different groups within it are blaming each other. Particularly often the criticism, from both left and right, is addressed to a vaguely defined social entity of “liberal protesters”, sometimes also denoted with labels such as “creative class”, “intelligentsia”, and “neoliberal establishment”. It is the criticized elements of protest practice which make me think that NGOers are also listed as part of the “liberal protesters”: recurrent reflection on the protest, bringing elements of creativity and celebration into it as well as the active coverage of NGOers’ participation in Instagram or Facebook.

Within Facebook in Belarus (and among Belarusians living abroad) the “creative class” is referred to as the “next enemy after the regime” and accused of usurping the representational space of the protest; the same goes for discursive marginalization of protest activities that differ from those of the creative class (e.g. street fighting). I have encountered twice the opinion that people who encourage others to go to protests with balloons and flowers in their hands are responsible for human victims of the protest.

Another direction of criticism in Facebook is of those who were running for president and were/are allegedly too pro-Russian or neoliberal, or both. International left does not show much sympathy to Belarusian protests. Slavoj Žižek stated, without any empirical reason, that ”The aim of the protests in cities like Minsk is to align the country with Western liberal-capitalist values“.1 Other leftist analysts were concerned, as of 17th August 2020, with the risks of workers being “indoctrinated” with “liberal and nationalist agenda” of a “broad liberal protest”.2 Omitted or mentioned in passing in most of those criticisms is the police violence. The scale of violence used by the police in Belarus on the first post-election days, 9-13 August 2020 “seems to have no analogues in the political history of Europe in the post-WWII period”.3 For details and figures regarding the violations of human rights in the first days after election one can consult the report of Human Rights Center “Viasna”.4

Since 9th of August the Belarusian regime clearly demonstrated features of an organized crime group (kidnapping and robbing people, damaging property), fascism (mass torture and sadistic humiliation of dissenters) and slave-owning system (forcing workers to stay and work at their workplaces). The protest does not have an economic agenda simply because people find it hard to talk about taxation, privatization, and even geopolitics in the country where the very ideas of personal safety, property, law, and citizenship have been systematically ignored for months already: as OMON5 comes to schools, as it forces factory workers to go on their shift, as it grabs people on their way to/from the supermarket. Most people in Belarus are protesting, first and foremost, against this harassment by the police.

NGOs in Belarus: work as a form of protest

On October 26, 2020, Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya announced the beginning of national strike in Belarus. Professional communities that I belong to — university lecturers, NGO workers, artists, civil activists, — were overwhelmingly in favour of this move and shared information about it. Literally all of the cafes and bars where we usually eat were closed on that Monday, as well as other places from which we used to consume services and buy goods. Minsk Urban Platform, an NGO that I am part of, was puzzled: do we work or do we strike? Do we work if none of the help that we rely on comes from the Belarusian state? Do we work if the entire NGO labour in Belarus is in fact an act of permanent protest? Do we relocate from Belarus to a safer place in order to do our work better? And how do we respond to the criticism of any decision we’d take in this situation? These practical questions pushed me to analyze the position of NGO workers within the ongoing Belarusian protest.

Of course, there is no “NGO worker” or third sector worker in Belarus — it is a cloud of diverse positions, nominations, and even identities. However, for the purposes of this text I can try to specify who it is not. First of all, here I do not refer to workers of GONGOs, which try to substitute or fake civil society in Belarus.6 Neither I consider those whom Alena Minchenia called “professional protesters”7 — members of opposition’s political organizations. The rest are mainly people active within centres, platforms, associations, and unions for human rights, specifically rights of vulnerable groups, informal education, social inclusion, environmental protection, sustainable mobility, etc.

Due to the vulnerability of these people in Belarus today, I will mention no names below. For instance, if the Facebook event is dedicated to help Belarusians abroad you cannot even be sure who you can invite to it without a risk to compromise them.

While aware of the criticism of NGO-ization, more specifically, of NGO becoming “a well-mannered, reasonable, salaried, 9-to-5 job”, I would object that in Belarus it has been transforming in the opposite direction over the last years. Well, what does it mean to be an NGO worker in Belarus? First of all, no funding from the Belarusian government and an increasingly bureaucratized procedure of receiving assistance from abroad. Obviously, with no working contracts, Belarusian NGOers are mostly people living from one project to another, without any pension fund contributions and guarantees of income for a next calendar year (a rare project envisions financial support for longer than 12 months) — and in permanent fear of imprisonment. NGO workers in Belarus are less likely to have children — a subjective observation I cannot comment in this text — although they usually have parents (who often need care). General unpredictability of life scenarios and absence of employment warrants makes it irrelevant for them to buy cars on credit or deal with the real estate mortgage (I believe, credits and mortgages make factory workers more vulnerable and helpless against dismissal — Belarusian factories workers are not an exception). NGO workers in Belarus are often hard to distinguish from volunteers (and there are no working unions for them); moreover, without a working contract you can’t be fired.

To these characteristics one can add the low prestige of NGOs in Belarusian society. In Belarus NGO workers are often called “grant-eaters” — and they do depend on foreign grants (which take lots of nerves, papers, and months to be registered), because Belarusian state does not bother with spending on education and science, as well as culture, ecology, art and many other things that require long term investment and do not bring direct rent.

NGO workers are indeed more likely to have Schengen visas or residence permits but it is simply because their activity requires constant improvement of qualification and exchange of experience with colleagues abroad. Having to work in the highly bureaucratized, corrupt, and violent environment, these people are exposed to burn-outs, and leaving the country for a week or two can be a quicker and cheaper way to protect mental health than going to a therapist.

NGO workers do often emigrate from Belarus but not even because they can hardly count on a career or comprehensive self-realization here. In most cases, they leave the country because they cannot count on safety on its territory.

What to do in Belarus in 2020?

In 2020, many NGO offices which made a conscious decision to close for quarantine in March, remain closed because of the fears that officers from GUBAZiK (Interior Ministry’s Main Directorate for Combating Organized Crime and Corruption) might come with a raid. From May till August 2020, dozens of my NGO colleagues were involved in pre-election campaigns as collectors of signatures for alternative candidates; majority of them spent some time disseminating information about elections; quite a few decided to be independent observers at the elections.

Due to the coronavirus pandemic and unprecedented political mobilization of the Belarusian society, many NGOers not only stayed in Belarus over pre- and post-election months but were also actively engaged in the protest. On the first post-election days, organizations wrote and signed a public letter against police violence. They made many posters to support those who were on strike, which they donated to the solidarity foundations. Most of them go to protests; especially to Sunday rallies — which is the minimum expected. If someone doesn’t go to protests, he or she often tries to find excuses for that. The community tries to raise awareness that every protester has a set of privileges and vulnerabilities which affect whether or not they can participate in the street protests. Despite this rational message, missing the protest marches is a frequent cause of frustration and self-conviction. Meanwhile, dozens of my Belarusian NGO friends went through detention over the last three months. A colleague who did urban research on improvement of public services has been under criminal trial since July. He was thrown into prison only because other protesters did not give him out to OMON during one of the peaceful demonstrations.

All of that doesn’t mean that the Belarusian NGOs stopped the implementations of their planned projects in 2020. “Okay, the protest is going to be our new normal for some time, but who will do my work? Who will develop our work in Belarus?” — says a colleague of mine, who works for social inclusion and accessibility. In Belarus you do not expect any state authority to do that work. So, for many NGOers, 2020 is torn between the realization of projects (that they often have to re-design with COVID-19 in mind) and the participation in the protest movement.

Like everyone else, NGO workers are claiming the right to physical safety and justice by going to the streets and, incredibly often, to jail. Many of them clearly articulate that they want the protests to raise economic demands and conversations about inequality and precarity. However, so far the gap between a person with the keyboard and a person with the rock-drill in Belarus is much smaller than the gap between siloviki8 in balaclavas and all the rest. This is the most significant inequality which makes us all precarious, and we do not know for how long this situation will last — this circumstance is largely omitted by the political analysts of different orientations.

Can I quit?

A certain symbolic line is drawn in discussions by both sides, those Belarusian NGO-workers who physically left Belarus and those who stayed in the country. Those who remained in Belarus respond to the criticism with the most radical argument of these days which is hard to object to — to be present here.

Those who for different reasons make a decision to leave the country, obviously feel the need to explain why they do so. Some Belarusians relocate immediately after being beaten by the riot police and after the administrative detention for going to the streets with flowers and posters, and/or after visits by the “police” at their homes or offices, and/or after being repeatedly “invited for a talk” to a local police office — via a phone call from a hidden number because in Belarus the “policemen” are not even bothered to officially summon to court.

In a way, the Belarusian citizens are privileged exodists: they are white and they do not have to cross a sea to enter another country. However, it is pandemic time and borders are closed. As of 30th October you can only cross borders with Latvia, Lithuania, and Poland if you have a type D visa or a residence permit from those countries. In certain cases you will not be able to return to Belarus because this state decides to not let its own citizens back in.9 It is more complicated with Russia as there is no type D visa for Belarusian citizens. However, Russia allows Belarus citizens if they have an appointment for a medical treatment or visit close relatives there. As of the late October, Ukraine is one of the few remaining destinations Belarusian citizens can travel to without a visa, but is very likely that this possibility might be interrupted at any moment with the introduction of new anti-coronavirus regulations.

The dread of the moment when Lukashenka’s words were mistaken as a decision to close borders with Lithuania and Poland is still present: for many, the impossibility of leaving the country is the last stop on the way to totalitarianism.

After weeks of ethical hesitations and despite the dangers of the coronavirus, many eventually take a bus.

And I started thinking: Maybe I have spent not enough time in jail? It was only 15 days but some got 30, and some were there for months. Am I such a coward to sneak after that? May I allow myself to leave Minsk now? Have I deserved this right to be outside of Belarus? — this kind of monologue you can imagine in Kyiv, Warsaw, Vilnius and other cities where Belarusian NGO workers and activists go in 2020. I have heard a few myself, and several more were recited by “friends of my friends”.

After leaving Belarus and coming to a safer place, the worst question you can hear is “Are you in Minsk now?” Siarhei Čaly, a Belarusian economist, admitted he was “a bit irritated with Belarusians flooding Warsaw, Kyiv, and Vilnius’. Leaving Minsk is less cool than it has ever been before, and you do not post Instagram stories from Kyiv.

Furthermore, you have no idea of how to talk to your friends in Minsk. Should you persuade them to take further care of themselves and leave the country? Or, rather, do you cheer them up and thank them for what they are doing?

An emotional shelter for some relocated Belarusians has been the “we work you strike” principle. “It is only my work which helps me not to go mad here”, admits a colleague on Instagram, after spending her seventh week outside of Belarus. Taking antidepressants and visiting a therapist is discussed daily, but my colleagues prefer to donate to Belarusian crowdfunding campaigns.

Some people are coming back to Belarus right now, during the last days of October. A colleague with Polish card; another colleague without Polish card; one more colleague who left Minsk “for a short weekend retreat only”, and so on. Belarusians can also be detained when entering the country, as it happened to a political prisoner Ihar Alinievič on the 30th of October. However, as a friend of mine recently put it, “at some point the fear of Belarusian prison is so strong that the only way to overcome it is to be in that prison”.

Thus, the unidimensional systems of coordinates, including the left-right political spectrum, fall short to describe the political composition of the Belarusian protest. The new Belarus is being constructed from multiple epistemic standpoints: by those attentively observing and those participating, by those taking care and those showing courage. Plurality of these standpoints is heuristic and produces the situated knowledge, in a feminist tradition of Donna Haraway: we can better understand what it means to be in Belarus by sharing ethnography of it to those who are not there. Within Belarus, an ability to look from multiple standpoints is crucial for understanding the imbalances of power and force that are causing violence and traumatizing the society. After all, the construction of Belarus is occurring without the method, as an exercise of Feyerabend’s epistemological anarchism, where “everything goes”. No single protest strategy can pretend to be the key one; and importantly, not a single group can carry responsibility for its success. Every protester in Belarus is a bit of an NGO worker these days, a participant of labor (work, not war) for change, a pioneer in multiple forms of “being there” and “protesting well enough”.

November 10, 2020

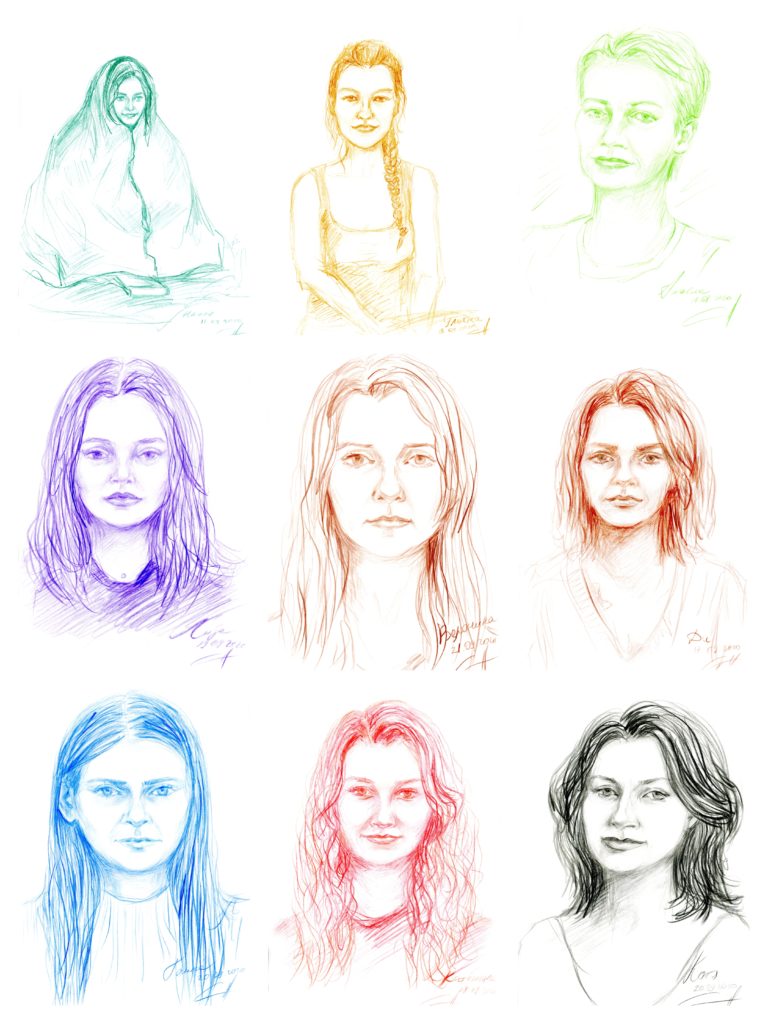

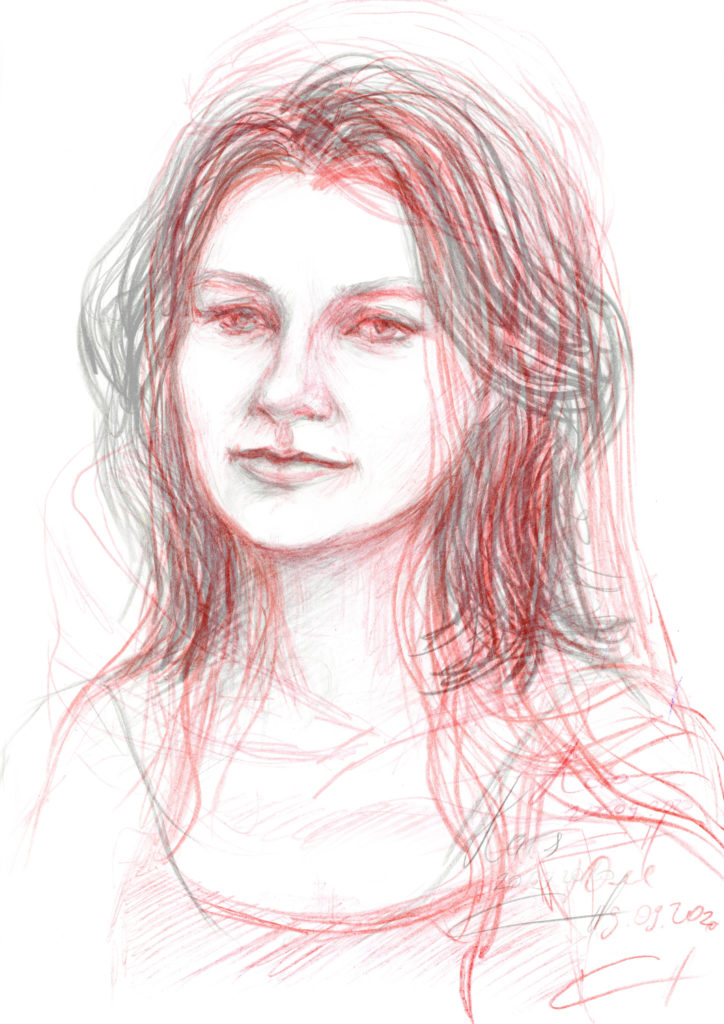

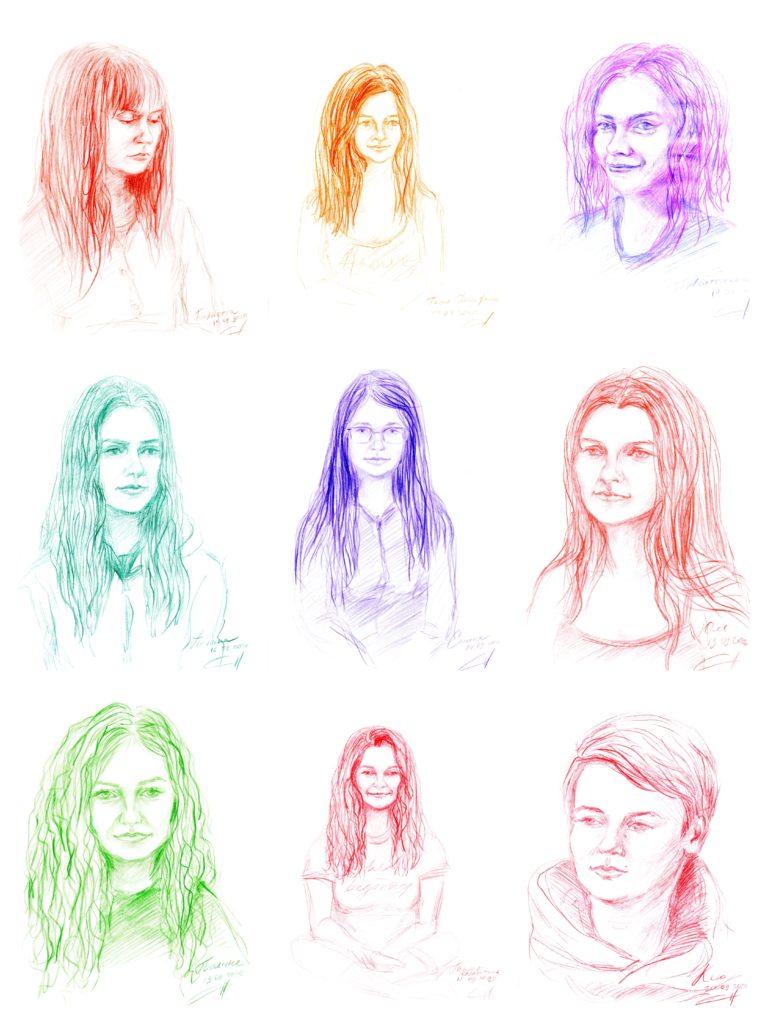

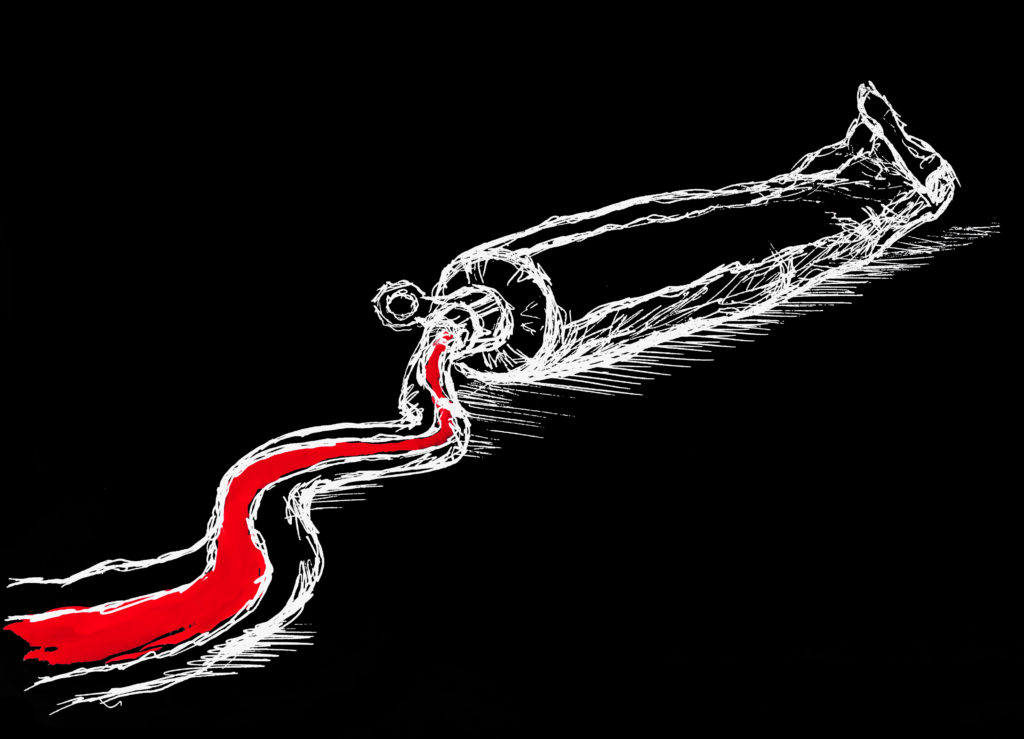

Cover on the main page: Iłla Jeraševič

-

Zizek, Slavoj, 2020. “Belarus’s problems won’t vanish when Lukashenko goes – victory for democracy also comes at a price.” The Independent, 24 August, 2020. https://www.independent.co.uk/voices/belarus-election-lukashenko-minsk-protests-democracy-freedom-coronavirus-a9685816.html↩

-

Kunitskaya, Ksenia & Vitaly Shkurin, 2020. “In Belarus, the Left Is Fighting to Put Social Demands at the Heart of the Protests.” Interview by Volodymyr Artiukh. Jacobin, 17 August, 2020. https://www.jacobinmag.com/2020/08/belarus-protests-lukashenko-minsk↩

-

“Belarus: The Birth of a Nation or Absorption by Putin’s Empire.” ISANS, September 14, 2020. https://isans.org/analysis-en/policy-papers-en/belarus-the-birth-of-a-nation-or-absorption-by-putins-empire.html ↩

-

“Human Rights Situation in Belarus: August 2020.” Viasna, September 2, 2020. http://spring96.org/en/news/99352/ ↩

-

The law enforcement agency in Belarus, which is considered to be the republic’s riot police. [ed.]↩

-

Matchanka, Anastasiya. “Substitution of Civil Society in Belarus: Government-Organised Non-Governmental Organisations.” Journal of Belarusian Studies 7, no. 2 (2014): 67-94.↩

-

Minchenia, Alena. “Belarusian Professional Protesters in the Structure of Democracy Promotion: Enacting Politics, Reinforcing Divisions.” Conflict and Society 6, no. 1 (2020): 218-235)↩

-

Literally translated as “people of force” or “strongmen”. Siloviki are members of security services police and armed forces.↩

-

On August 31st 2020 Tadevuš Kandrusievič, a Belarusian prelate of the Catholic Church, was prevented from entering Belarus after visiting Poland, despite being a Belarusian citizen. On November 1st there were reports of Belarusian students studying abroad denied entry to Belarus.↩